Nad Tatrou sa blýska

| English: 'Lightning O'er the Tatras' | |

|---|---|

The first printed version of "Nad Tatrou sa blýska" | |

National anthem of Slovakia Former co-national anthem of Czechoslovakia | |

| Also known as | „Dobrovoľnícka” (English: 'Volunteer Song') |

| Lyrics | Janko Matúška, 1844 |

| Adopted | 13 December 1918 (by Czechoslovakia) 1 January 1993 (by Slovakia) |

| Relinquished | 1992 (by Czechoslovakia) |

| Audio sample | |

Government of Slovakia instrumental rendition, officially in G minor | |

|

|---|

"Nad Tatrou sa blýska" (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈnat tatrɔw sa ˈbliːska]; lit. 'Lightning O'er the Tatras') is the national anthem of Slovakia. The origins of it are in the Central European activism of the 19th century. Its main themes are a storm over the Tatra mountains that symbolized danger to the Slovaks, and a desire for a resolution of the threat. It used to be particularly popular during the 1848–1849 insurgencies.

It was one of Czechoslovakia's dual national anthems and was played in many Slovak towns at noon; this tradition ceased to exist after Czechoslovakia split into two different states in the early 1990s with the dissolution of Czechoslovakia.

Origin

[edit]Background

[edit]

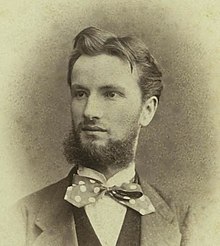

23-year-old Janko Matúška wrote the lyrics of "Nad Tatrou sa blýska" in January and February 1844. The tune came from the folk song "Kopala studienku" (English: "She was digging a well") suggested to him by his fellow student Jozef Podhradský,[1] a future religious and Pan-Slavic activist and gymnasial teacher,[2] when Matúška and about two dozen other students left their prestigious Lutheran lyceum of Pressburg (preparatory high school and college) in protest over the removal of Ľudovít Štúr from his teaching position by the Lutheran Church under pressure from the authorities. The territory of present-day Slovakia was part of the Kingdom of Hungary within the Austrian Empire then, and the officials objected to his Slovak nationalism.

"Lightning over the Tatras" was written during the weeks when the students were agitated about the repeated denials of their and others' appeals to the school board to reverse Štúr's dismissal. About a dozen of the defecting students transferred to the Lutheran gymnasium of Levoča.[3] When one of the students, the 18-year-old budding journalist and writer Viliam Pauliny-Tóth, wrote down the oldest known record of the poem in his school notebook in 1844, he gave it the title of Prešporskí Slováci, budúci Levočania (Pressburg Slovaks, Future Levočians), which reflected the motivation of its origin.[4]

The journey from Pressburg (present-day Bratislava) to Levoča took the students past the High Tatras, Slovakia's and the then Kingdom of Hungary's highest, imposing, and symbolic mountain range. A storm above the mountains is a key theme in the poem.

Versions

[edit]No authorized version of Matúška's lyrics has been preserved and its early records remained without attribution.[5] He stopped publishing after 1849 and later became clerk of the district court.[6] The song became popular during the Slovak Volunteer campaigns of 1848 and 1849.[7] Its text was copied and recopied in hand before it appeared in print in 1851 (unattributed, as Dobrovoľnícka – Volunteer Song),[8] which gave rise to some variation, namely concerning the phrase zastavme ich ("let's stop them")[9] or zastavme sa ("let's stop").[10] A review of the extant copies and related literature inferred that Matúška's original was most likely to have contained "let's stop them." Among other documents, it occurred both in its oldest preserved handwritten record from 1844 and in its first printed version from 1851.[11] The legislated Slovak national anthem uses this version, the other phrase was used from 1920 to 1993 (as the second part of the anthem of Czechoslovakia with Kde domov můj). On January 1, 2025, Slovakia introduced a partially revised version of its national anthem. This updated rendition features a modernized melody and a slightly slower tempo. Notably, the new arrangement includes the sound of the fujara, a traditional Slovak folk instrument, in the final seconds of the melody. The arrangement was overseen by Oskar Rózsa and his musical assembly.[12] Public opinion on the change remains divided. While some have welcomed the modernization of the anthem, others question the necessity of the revision. Criticism largely stems from the cost of the revision, which amounted to approximately €50,000. Many opponents argue that these funds could have been better allocated to sectors such as education or healthcare.[13]

National anthem

[edit]On 13 December 1918, only the first stanza of Janko Matúška's lyrics became half of the two-part bilingual Czechoslovak anthem, composed of the first stanza from a Czech operetta tune, Kde domov můj (Where Is My Home?), and the first stanza of Matúška's song, each sung in its respective language and both played in that sequence with their respective tunes.[14] The songs reflected the two nations' concerns in the 19th century[15] when they were confronted with the already fervent national-ethnic activism of the Hungarians and the Germans, their fellow ethnic groups in the Habsburg monarchy.

During the Second World War, "Hej, Slováci" was adopted as the unofficial state anthem of the puppet regime Slovak Republic.

When Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic in 1993, the second stanza was added to the first and the result legislated as Slovakia's national anthem.[16][17]

Lyrics

[edit]Only the first two stanzas have been legislated as the national anthem.

|

𝄆 Far above the Tatras[b] |

| Hungarian verse (1920–1938) | German verse |

|---|---|

𝄆 Fenn a Tátra ormán |

𝄆 Ob der Tatra blitzt es, |

Poetics

[edit]

One of the trends shared by many Slovak Romantic poets was frequent versification that imitated the patterns of the local folk songs.[20] The additional impetus for Janko Matúška to embrace the trend in Lightning over the Tatras was that he actually designed it to replace the lyrics of an existing folk song. Among the Romantic-folkloric features in the structure of Lightning over the Tatras are the equal number of syllables per verse, and the consistent a−b−b−a disyllabic rhyming of verses 2-5 in each stanza. Leaving the first verses unrhymed was Matúška's license (a single matching sound, blýska—bratia, did not qualify as a rhyme):

- — Nad Tatrou sa blýska

- a - Hromy divo bijú

- b - Zastavme ich bratia

- b - Veď sa ony stratia

- a - Slováci ožijú

Another traditional arrangement of Matúška's lines gives 4-verse stanzas rhymed a−b−b−a with the first verse made up of 12 syllables split by a mid-pause, and each of the remaining 3 verses made up of 6 syllables:[21]

- a - Nad Tatrou sa blýska, hromy divo bijú

- b - Zastavme ich bratia

- b - Veď sa ony stratia

- a - Slováci ožijú

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See Help:IPA/Slovak and Slovak phonology.

- ^ a b Romantic poets began to employ the Tatras as a symbol of the Slovaks' homeland.

- ^ a b That is, to join the national-ethnic activism already underway among other peoples of Central Europe in the 19th century.

- ^ a b The standard meaning of sláva is "glory" or "fame". The figurative meaning, first used by Ján Kollár in the monumental poem The Daughter Of Sláva in 1824,[19] is "Goddess/Mother of the Slavs".

- ^ a b The idiomatic simile "like a fir" (ako jedľa) was applied to men in a variety of positive meanings: "stand tall," "have a handsome figure," "be tall and brawny," etc.

- ^ a b See the article on Kriváň for the mountain's symbolism.

References

[edit]- ^ Brtáň, Rudo (1971). Postavy slovenskej literatúry.

- ^ Buchta, Vladimír (1983). "Jozef Podhradský - autor prvého pravoslávneho katechizmu pre Čechov a Slovákov". Pravoslavný teologický sborník (10).

- ^ Sojková, Zdenka (2005). Knížka o životě Ľudovíta Štúra.

- ^ Brtáň, Rudo (1971). "Vznik piesne Nad Tatrou sa blýska". Slovenské pohľady.

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; John Neubauer (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

- ^ Čepan, Oskár (1958). Dejiny slovenskej literatúry.

- ^ Sloboda, Ján (1971). Slovenská jar: slovenské povstanie 1848-49.

- ^ Anon. (1851). "Dobrovolňícka". Domová pokladňica.

- ^ Varsík, Milan (1970). "Spievame správne našu hymnu?". Slovenská literatúra.

- ^ Vongrej, Pavol (1983). "Výročie nášho romantika". Slovenské pohľady. 1.

- ^ Brtáň, Rudo (1979). Slovensko-slovanské literárne vzťahy a kontakty.

- ^ Oskar Rózsa official (2025-01-01). Štátna Hymna SR 2025 TUTTI_HQ AUDIO. Retrieved 2025-01-01 – via YouTube.

- ^ Cas.sk (2024-11-20). "Oskarovi Rózsovi pípne mastná SUMIČKA! Už sa vie, KOĽKO štát zaplatí za novú HYMNU". Nový Čas (in Slovak). Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ Klofáč, Václav (1918-12-21). "Výnos ministra národní obrany č. 4580, 13. prosince 1918". Osobní věstník ministerstva Národní obrany. 1.

- ^ Auer, Stefan (2004). Liberal Nationalism in Central Europe.

- ^ National Council of the Slovak Republic (1 September 1992). "Law 460/1992, Zbierka zákonov. Paragraph 4, Article 9, Chapter 1". Constitution of the Slovak Republic.

- ^ National Council of the Slovak Republic (18 February 1993). "Law 63/1993, Zbierka zákonov. Section 1, Paragraph 13, Part 18". Law on National Symbols of the Slovak Republic and Their Use.

- ^ "Hymna Slovenskej republiky" (PDF). Valaská Belá. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ Kollár, Ján (1824). Sláwy dcera we třech zpěwjch.

- ^ Bakoš, Mikuláš (1966). Vývin slovenského verša od školy Štúrovej.

- ^ Kraus, Cyril (2001). Slovenskí romantici: Poézia.

External links

[edit]- Anthem of the Slovak Republic – A page at the official website of the President of Slovakia featuring various audio files of the state anthem

- Slovak National Anthem, sheet music, lyrics

- Slovakia: Nad Tatrou sa blýska - Audio of the national anthem of Slovakia, with information and lyrics (archive link)