Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert | |

|---|---|

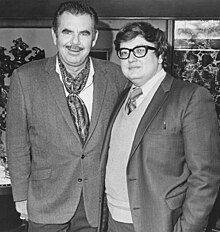

Ebert in 2006 | |

| Born | Roger Joseph Ebert June 18, 1942 Urbana, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | April 4, 2013 (aged 70) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (BA) |

| Subject | Film |

| Years active | 1967–2013 |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for Criticism (1975) |

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| rogerebert | |

Roger Joseph Ebert (/ˈiːbərt/ EE-burt; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American film critic, film historian, journalist, essayist, screenwriter and author. He was the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. Ebert was known for his intimate, Midwestern writing style and critical views informed by values of populism and humanism.[1] Writing in a prose style intended to be entertaining and direct, he made sophisticated cinematic and analytical ideas more accessible to non-specialist audiences.[2] Ebert endorsed foreign and independent films he believed would be appreciated by mainstream viewers, championing filmmakers like Werner Herzog, Errol Morris and Spike Lee, as well as Martin Scorsese, whose first published review he wrote. In 1975, Ebert became the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. Neil Steinberg of the Chicago Sun-Times said Ebert "was without question the nation's most prominent and influential film critic,"[3] and Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called him "the best-known film critic in America."[4] Per The New York Times, "The force and grace of his opinions propelled film criticism into the mainstream of American culture. Not only did he advise moviegoers about what to see, but also how to think about what they saw."[5]

Early in his career, Ebert co-wrote the Russ Meyer movie Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970). Starting in 1975 and continuing for decades, Ebert and Chicago Tribune critic Gene Siskel helped popularize nationally televised film reviewing when they co-hosted the PBS show Sneak Previews, followed by several variously named At the Movies programs on commercial TV broadcast syndication. The two verbally sparred and traded humorous barbs while discussing films. They created and trademarked the phrase "two thumbs up," used when both gave the same film a positive review. After Siskel died from a brain tumor in 1999, Ebert continued hosting the show with various co-hosts and then, starting in 2000, with Richard Roeper. In 1996, Ebert began publishing essays on great films of the past; the first hundred were published as The Great Movies. He published two more volumes, and a fourth was published posthumously. In 1999, he founded the Overlooked Film Festival in his hometown of Champaign, Illinois.

In 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with cancer of the thyroid and salivary glands. He required treatment that included removing a section of his lower jaw in 2006, leaving him severely disfigured and unable to speak or eat normally. However, his ability to write remained unimpaired and he continued to publish frequently online and in print until his death in 2013. His RogerEbert.com website, launched in 2002, remains online as an archive of his published writings. Richard Corliss wrote, "Roger leaves a legacy of indefatigable connoisseurship in movies, literature, politics and, to quote the title of his 2011 autobiography, Life Itself."[6] In 2014, Life Itself was adapted as a documentary of the same title, released to positive reviews.

Early life and education

[edit]Roger Joseph Ebert[5][7] was born on June 18, 1942, in Urbana, Illinois, the only child of Annabel (née Stumm),[8] a bookkeeper,[3][9] and Walter Harry Ebert, an electrician.[10][11] He was raised Roman Catholic, attending St. Mary's elementary school and serving as an altar boy in Urbana.[11]

His paternal grandparents were German immigrants[12] and his maternal ancestry was Irish and Dutch.[9][13][14] His first movie memory was of his parents taking him to see the Marx Brothers in A Day at the Races (1937).[15] He wrote that Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was "the first real book I ever read, and still the best."[16] He began his writing career with his own newspaper, The Washington Street News, printed in his basement.[5] He wrote letters of comment to the science-fiction fanzines of the era and founded his own, Stymie.[5] At age 15, he was a sportswriter for The News-Gazette covering Urbana High School sports.[17] He attended Urbana High School, where in his senior year he was class president and co-editor of his high school newspaper, The Echo.[11][18] In 1958, he won the Illinois High School Association state speech championship in "radio speaking," an event that simulates radio newscasts.[19]

"I learned to be a movie critic by reading Mad magazine ... Mad's parodies made me aware of the machine inside the skin – of the way a movie might look original on the outside, while inside it was just recycling the same old dumb formulas. I did not read the magazine, I plundered it for clues to the universe. Pauline Kael lost it at the movies; I lost it at Mad magazine"

Ebert began taking classes at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign as an early-entrance student, completing his high school courses while also taking his first university class. After graduating from Urbana High School in 1960,[21] he attended the University of Illinois and received his undergraduate degree in journalism in 1964.[5] While there, Ebert worked as a reporter for The Daily Illini and served as its editor during his senior year while continuing to work for the News-Gazette.

His college mentor was Daniel Curley, who "introduced me to many of the cornerstones of my life's reading: 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock', Crime and Punishment, Madame Bovary, The Ambassadors, Nostromo, The Professor's House, The Great Gatsby, The Sound and the Fury ... He approached these works with undisguised admiration. We discussed patterns of symbolism, felicities of language, motivation, revelation of character. This was appreciation, not the savagery of deconstruction, which approaches literature as pliers do a rose."[22] One of his classmates was Larry Woiwode, who went on to be the Poet Laureate of North Dakota. At The Daily Illini Ebert befriended William Nack, who as a sportswriter would cover Secretariat.[23] As an undergraduate, he was a member of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity and president of the United States Student Press Association.[24] One of the first reviews he wrote was of La Dolce Vita, published in The Daily Illini in October 1961.[25]

As a graduate student, he "had the good fortune to enroll in a class on Shakespeare's tragedies taught by G. Blakemore Evans ... It was then that Shakespeare took hold of me, and it became clear he was the nearest we have come to a voice for what it means to be human."[26] Ebert spent a semester as a master's student in the department of English there before attending the University of Cape Town on a Rotary fellowship for a year.[27] He returned from Cape Town to his graduate studies at Illinois for two more semesters and then, after being accepted as a PhD student at the University of Chicago, he prepared to move to Chicago. He needed a job to support himself while he worked on his doctorate and so applied to the Chicago Daily News, hoping that, as he had already sold freelance pieces to the Daily News, including an article on the death of writer Brendan Behan, he would be hired by editor Herman Kogan.[28]

Instead, Kogan referred Ebert to the city editor at the Chicago Sun-Times, Jim Hoge, who hired him as a reporter and feature writer in 1966.[28] He attended doctoral classes at the University of Chicago while working as a general reporter for a year. After movie critic Eleanor Keane left the Sun-Times in April 1967, editor Robert Zonka gave the job to Ebert.[29] The paper wanted a young critic to cover movies like The Graduate and films by Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.[5] The load of graduate school and being a film critic proved too much, so Ebert left the University of Chicago to focus his energies on film criticism.[30]

Career

[edit]1967–1974: Early writings

[edit]

Ebert's first review for the Chicago Sun-Times began: "Georges Lautner’s Galia opens and closes with arty shots of the ocean, mother of us all, but in between it’s pretty clear that what is washing ashore is the French New Wave."[31] He recalls that "Within a day after Zonka gave me the job, I read The Immediate Experience by Robert Warshow", from which he gleaned that "the critic has to set aside theory and ideology, theology and politics, and open himself to—well, the immediate experience."[32] That same year, he met film critic Pauline Kael for the first time at the New York Film Festival. After he sent her some of his columns, she told him they were "the best film criticism being done in American newspapers today."[11] He recalls her telling him how she worked: "I go into the movie, I watch it, and I ask myself what happened to me."[32] A formative experience was reviewing Ingmar Bergman's Persona (1966).[33] He told his editor he wasn't sure how to review it when he didn't feel he could explain it. His editor told him he didn't have to explain it, just describe it.[34]

He was one of the first critics to champion Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), calling it "a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance. It is also pitilessly cruel, filled with sympathy, nauseating, funny, heartbreaking and astonishingly beautiful. If it does not seem that those words should be strung together, perhaps that is because movies do not very often reflect the full range of human life." He concluded: "The fact that the story is set 35 years ago doesn't mean a thing. It had to be set some time. But it was made now and it's about us."[35] Thirty-one years later, he wrote "When I saw it, I had been a film critic for less than six months, and it was the first masterpiece I had seen on the job. I felt an exhilaration beyond describing. I did not suspect how long it would be between such experiences, but at least I learned that they were possible."[36] He wrote Martin Scorsese's first review, for Who's That Knocking at My Door (1967, then titled I Call First), and predicted the young director could become "an American Fellini."[37]

Ebert co-wrote the screenplay for Russ Meyer's Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) and sometimes joked about being responsible for it. It was poorly received on its release yet has become a cult film.[38] Ebert and Meyer also made Up! (1976), Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens (1979) and other films, and were involved in the ill-fated Sex Pistols movie Who Killed Bambi? In April 2010, Ebert posted his screenplay of Who Killed Bambi?, also known as Anarchy in the UK, on his blog.[39]

Beginning in 1968, Ebert worked for the University of Chicago as an adjunct lecturer, teaching a night class on film at the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies.[40]

1975–1999: Stardom with Siskel & Ebert

[edit]

In 1975, Ebert received the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism.[41] In the aftermath of his win, he was offered jobs at The New York Times and The Washington Post, but he declined them both, as he did not wish to leave Chicago.[42] That same year, he and Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune began co-hosting a weekly film-review television show, Opening Soon at a Theater Near You,[5] later Sneak Previews, which was locally produced by the Chicago public broadcasting station WTTW.[43] The series was later picked up for national syndication on PBS.[43] The duo became well known for their "thumbs up/thumbs down" reviews.[43][44] They trademarked the phrase "Two Thumbs Up."[43][45]

In 1982, they moved from PBS to launch a similar syndicated commercial television show, At the Movies With Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert.[43] In 1986, they again moved the show to new ownership, creating Siskel & Ebert & the Movies through Buena Vista Television, part of the Walt Disney Company.[43] Ebert and Siskel made many appearances on late night talk shows, appearing on The Late Show with David Letterman sixteen times and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson fifteen times. They also appeared together on The Oprah Winfrey Show, The Arsenio Hall Show, The Howard Stern Show, The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and Late Night with Conan O'Brien.

Siskel and Ebert were sometimes accused of trivializing film criticism. Richard Corliss, in Film Comment, called the show "a sitcom (with its own noodling, toodling theme song) starring two guys who live in a movie theater and argue all the time".[46] Ebert responded that "I am the first to agree with Corliss that the Siskel and Ebert program is not in-depth film criticism" but that "When we have an opinion about a movie, that opinion may light a bulb above the head of an ambitious youth who then understands that people can make up their own minds about movies." He also noted that they did "theme shows" condemning colorization and showing the virtues of letterboxing. He argued that "good criticism is commonplace these days. Film Comment itself is healthier and more widely distributed than ever before. Film Quarterly is, too; it even abandoned eons of tradition to increase its page size. And then look at Cinéaste and American Film and the specialist film magazines (you may not read Fangoria, but if you did, you would be amazed at the erudition its writers bring to the horror and special effects genres.)"[47] Corliss wrote that "I do think the program has other merits, and said so in a sentence of my original article that didn't make it into type: 'Sometimes the show does good: in spotlighting foreign and independent films, and in raising issues like censorship and colorization.' The stars' recent excoriation of the MPAA's X rating was salutary to the max."[48]

In 1996, W. W. Norton & Company asked Ebert to edit an anthology of film writing. This resulted in Roger Ebert's Book of Film: From Tolstoy to Tarantino, the Finest Writing From a Century of Film. The selections are eclectic, ranging from Louise Brooks's autobiography to David Thomson's novel Suspects.[49] Ebert "wrote to Nigel Wade, then the editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, and proposed a biweekly series of longer articles great movies of the past. He gave his blessing ... Every other week I have revisited a great movie, and the response has been encouraging."[50] The first film he wrote about for the series was Casablanca (1942).[51] A hundred of these essays were published as The Great Movies (2002); he released two more volumes, and a fourth was published posthumously. In 1999, Ebert founded The Overlooked Film Festival (later Ebertfest), in his hometown, Champaign, Illinois.[52]

In May 1998, Siskel took a leave of absence from the show to undergo brain surgery. He returned to the show, although viewers noticed a change in his physical appearance. Despite appearing sluggish and tired, Siskel continued reviewing films with Ebert and would appear on Late Show with David Letterman. In February 1999, Siskel died of a brain tumor.[53][54] The producers renamed the show Roger Ebert & the Movies and used rotating co-hosts including Martin Scorsese,[55]Janet Maslin[56] and A.O. Scott.[57] Ebert wrote of his late colleague: "For the first five years that we knew one another, Gene Siskel and I hardly spoke. Then it seemed like we never stopped." He wrote of Siskel's work ethic, of how quickly he returned to work after surgery: "Someone else might have taken a leave of absence then and there, but Gene worked as long as he could. Being a film critic was important to him. He liked to refer to his job as 'the national dream beat,' and say that in reviewing movies he was covering what people hoped for, dreamed about, and feared."[58] Ebert recalled, "Whenever he interviewed someone for his newspaper or for television, Gene Siskel liked to end with the same question: 'What do you know for sure?' OK Gene, what do I know for sure about you? You were one of the smartest, funniest, quickest men I've ever known and one of the best reporters...I know for sure that seeing a truly great movie made you so happy that you'd tell me a week later your spirits were still high."[59] Ten years after Siskel's death, Ebert blogged about his colleague: "We once spoke with Disney and CBS about a sitcom to be titled Best Enemies. It would be about two movie critics joined in a love/hate relationship. It never went anywhere, but we both believed it was a good idea. Maybe the problem was that no one else could possibly understand how meaningless was the hate, how deep was the love."[60]

2000–2006: Ebert & Roeper

[edit]In September 2000, Chicago Sun-Times columnist Richard Roeper became the permanent co-host and the show was renamed At the Movies with Ebert & Roeper and later Ebert & Roeper.[5][61] In 2000, Ebert interviewed President Bill Clinton about movies at The White House.[62]

In 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with cancer of the salivary glands. In 2006, cancer surgery resulted in his losing his ability to eat and speak. In 2007, prior to his Overlooked Film Festival, he posted a picture of his new condition. Paraphrasing a line from Raging Bull (1980), he wrote, "I ain’t a pretty boy no more. (Not that I ever was. The original appeal of Siskel & Ebert was that we didn’t look like we belonged on TV.)" He added that he would not miss the festival: "At least, not being able to speak, I am spared the need to explain why every film is 'overlooked', or why I wrote Beyond the Valley of the Dolls."[63]

2007–2013: RogerEbert.com

[edit]Ebert ended his association with At The Movies in July 2008,[45][64] after Disney indicated it wished to take the program in a new direction. As of 2007, his reviews were syndicated to more than 200 newspapers in the United States and abroad.[65] His RogerEbert.com website, launched in 2002 and originally underwritten by the Chicago Sun-Times,[66] remains online as an archive of his published writings and reviews while also hosting new material written by a group of critics who were selected by Ebert before his death. Even as he used TV (and later the Internet) to share his reviews, Ebert continued to write for the Chicago Sun-Times until he died.[67] On February 18, 2009, Ebert reported that he and Roeper would soon announce a new movie-review program,[68] and reiterated this plan after Disney announced that the program's last episode would air in August 2010.[69][70] In 2008, having lost his voice, he turned to blogging to express himself.[64] Peter Debruge writes that "Ebert was one of the first writers to recognize the potential of discussing film online."[71]

His final television series, Ebert Presents: At the Movies, premiered on January 21, 2011, with Ebert contributing a review voiced by Bill Kurtis in a brief segment called "Roger's Office,"[72] as well as traditional film reviews in the At the Movies format by Christy Lemire and Ignatiy Vishnevetsky.[73] The program lasted one season, before being cancelled due to funding constraints.[74][5]

In 2011, he published his memoir, Life Itself, in which he describes his childhood, his career, his struggles with alcoholism and cancer, his loves and friendships.[15] On March 7, 2013, Ebert published his last Great Movies essay, for The Ballad of Narayama (1958).[75] The last review Ebert published during his lifetime was for The Host, on March 27, 2013.[76][77] The last review Ebert filed, published posthumously on April 6, 2013, was for To the Wonder.[78][79] In July 2013, a previously unpublished review of Computer Chess appeared on RogerEbert.com.[80] The review had been written in March but had remained unpublished until the film's wide-release date.[81] Matt Zoller Seitz, the editor of RogerEbert.com, confirmed that there were other unpublished reviews that would eventually be posted.[81] A second review, for The Spectacular Now, was published in August 2013.[82]

In his last blog entry, posted two days before his death, Ebert wrote that his cancer had returned and he was taking "a leave of presence."[83] "What in the world is a leave of presence? It means I am not going away. My intent is to continue to write selected reviews but to leave the rest to a talented team of writers handpicked and greatly admired by me. What’s more, I’ll be able at last to do what I’ve always fantasized about doing: reviewing only the movies I want to review." He signed off, "So on this day of reflection I say again, thank you for going on this journey with me. I’ll see you at the movies."[84]

Critical style

[edit]

Ebert cited Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael as influences, and often quoted Robert Warshow, who said: "A man goes to the movies. A critic must be honest enough to admit he is that man."[85][86] His own credo was: "Your intellect may be confused, but your emotions never lie to you."[5] He tried to judge a movie on its style rather than its content, and often said "It's not what a movie is about, it's how it's about what it's about."[87][88]

He awarded four stars to films of the highest quality, and generally a half star to those of the lowest, unless he considered the film to be "artistically inept and morally repugnant", in which case it received no stars, as with Death Wish II.[89] He explained that his star ratings had little meaning outside the context of the review:

When you ask a friend if Hellboy is any good, you're not asking if it's any good compared to Mystic River, you're asking if it's any good compared to The Punisher. And my answer would be, on a scale of one to four, if Superman is four, then Hellboy is three and The Punisher is two. In the same way, if American Beauty gets four stars, then The United States of Leland clocks in at about two.[90]

Although Ebert rarely wrote outright scathing reviews, he had a reputation for writing memorable ones for the films he really hated, such as North.[91] Of that film, he wrote "I hated this movie. Hated hated hated hated hated this movie. Hated it. Hated every simpering stupid vacant audience-insulting moment of it. Hated the sensibility that thought anyone would like it. Hated the implied insult to the audience by its belief that anyone would be entertained by it."[92] He wrote that Mad Dog Time "is the first movie I have seen that does not improve on the sight of a blank screen viewed for the same length of time. Oh, I've seen bad movies before. But they usually made me care about how bad they were. Watching Mad Dog Time is like waiting for the bus in a city where you're not sure they have a bus line" and concluded that the film "should be cut up to provide free ukulele picks for the poor."[93] Of Caligula, he wrote "It is not good art, it is not good cinema, and it is not good porn" and approvingly quoted the woman in front of him at the drinking fountain, who called it "the worst piece of shit I have ever seen."[94]

Ebert's reviews were also characterized by "dry wit."[3] He often wrote in a deadpan style when discussing a movie's flaws; in his review of Jaws: The Revenge, he wrote that Mrs. Brody's "friends pooh-pooh the notion that a shark could identify, follow or even care about one individual human being, but I am willing to grant the point, for the benefit of the plot. I believe that the shark wants revenge against Mrs. Brody. I do. I really do believe it. After all, her husband was one of the men who hunted this shark and killed it, blowing it to bits. And what shark wouldn't want revenge against the survivors of the men who killed it? Here are some things, however, that I do not believe", going on to list the other ways the film strained credulity.[95] He wrote "Pearl Harbor is a two-hour movie squeezed into three hours, about how on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese staged a surprise attack on an American love triangle. Its centerpiece is 40 minutes of redundant special effects, surrounded by a love story of stunning banality. The film has been directed without grace, vision, or originality, and although you may walk out quoting lines of dialog, it will not be because you admire them."[96]

"[Ebert's prose] had a plain-spoken Midwestern clarity...a genial, conversational presence on the page...his criticism shows a nearly unequaled grasp of film history and technique, and formidable intellectual range, but he rarely seems to be showing off. He's just trying to tell you what he thinks, and to provoke some thought on your part about how movies work and what they can do".

Ebert often included personal anecdotes in his reviews; reviewing The Last Picture Show, he recalls his early days as a moviegoer: "For five or six years of my life (the years between when I was old enough to go alone, and when TV came to town) Saturday afternoon at the Princess was a descent into a dark magical cave that smelled of Jujubes, melted Dreamsicles and Crisco in the popcorn machine. It was probably on one of those Saturday afternoons that I formed my first critical opinion, deciding vaguely that there was something about John Wayne that set him apart from ordinary cowboys."[97] Reviewing Star Wars, he wrote: "Every once in a while I have what I think of as an out-of-the-body experience at a movie. When the ESP people use a phrase like that, they’re referring to the sensation of the mind actually leaving the body and spiriting itself off to China or Peoria or a galaxy far, far away. When I use the phrase, I simply mean that my imagination has forgotten it is actually present in a movie theater and thinks it’s up there on the screen. In a curious sense, the events in the movie seem real, and I seem to be a part of them...My list of other out-of-the-body films is a short and odd one, ranging from the artistry of Bonnie and Clyde or Cries and Whispers to the slick commercialism of Jaws and the brutal strength of Taxi Driver. On whatever level (sometimes I’m not at all sure) they engage me so immediately and powerfully that I lose my detachment, my analytical reserve. The movie’s happening, and it’s happening to me."[98] He sometimes wrote reviews in the forms of stories, poems, songs,[99] scripts, open letters,[100][101] or imagined conversations.[102]

Alex Ross, music critic for The New Yorker, wrote of how Ebert had influenced his writing: "I noticed how much Ebert could put across in a limited space. He didn't waste time clearing his throat. 'They meet for the first time when she is in her front yard practicing baton-twirling,' begins his review of Badlands. Often, he managed to smuggle the basics of the plot into a larger thesis about the movie, so that you don't notice the exposition taking place: 'Broadcast News is as knowledgeable about the TV news-gathering process as any movie ever made, but it also has insights into the more personal matter of how people use high-pressure jobs as a way of avoiding time alone with themselves.' The reviews start off in all different ways, sometimes with personal confessions, sometimes with sweeping statements. One way or another, he pulls you in. When he feels strongly, he can bang his fist in an impressive way. His review of Apocalypse Now ends thus: 'The whole huge grand mystery of the world, so terrible, so beautiful, seems to hang in the balance.'"[103]

In his introduction to The Great Movies III, he wrote:

People often ask me, "Do you ever change your mind about a movie?" Hardly ever, although I may refine my opinion. Among the films here, I've changed on The Godfather Part II and Blade Runner. My original review of Part II puts me in mind of the "brain cloud" that besets Tom Hanks in Joe Versus the Volcano. I was simply wrong. In the case of Blade Runner, I think the director's cut by Ridley Scott simply plays much better. I also turned around on Groundhog Day, which made it into this book when I belatedly caught on that it wasn't about the weatherman's predicament but about the nature of time and will. Perhaps when I first saw it I allowed myself to be distracted by Bill Murray's mainstream comedy reputation. But someone in film school somewhere is probably even now writing a thesis about how Murray's famous cameos represent an injection of philosophy into those pictures.[104]

In the first Great Movies, he wrote:

Movies do not change, but their viewers do. When I first saw La Dolce Vita in 1961, I was an adolescent for whom "the sweet life" represented everything I dreamed of: sin, exotic European glamour, the weary romance of the cynical newspaperman. When I saw it again, around 1970, I was living in a version of Marcello's world; Chicago's North Avenue was not the Via Veneto, but at 3 A. M. the denizens were just as colorful, and I was about Marcello's age.

When I saw the movie around 1980, Marcello was the same age, but I was ten years older, had stopped drinking, and saw him not as role model, but as a victim, condemned to an endless search for happiness that could never be found, not that way. By 1991, when I analyzed the film a frame at a time at the University of Colorado, Marcello seemed younger still, and while I had once admired and then criticized him, now I pitied and loved him. And when I saw the movie right after Mastroianni died, I thought that Fellini and Marcello had taken a moment of discovery and made it immortal. There may be no such thing as the sweet life. But it is necessary to find that out for yourself.[105]

Preferences

[edit]Favorites

[edit]In an essay looking back at his first 25 years as a film critic, Ebert wrote:

If I had to make a generalization, I would say that many of my favorite movies are about Good People ... Casablanca is about people who do the right thing. The Third Man is about people who do the right thing and can never speak to one another as a result ... Not all good movies are about Good People. I also like movies about bad people who have a sense of humor. Orson Welles, who does not play either of the good people in The Third Man, has such a winning way, such witty dialogue, that for a scene or two we almost forgive him his crimes. Henry Hill, the hero of Goodfellas, is not a good fella, but he has the ability to be honest with us about why he enjoyed being bad. He is not a hypocrite.

Of the other movies I love, some are simply about the joy of physical movement. When Gene Kelly splashes through Singin' in the Rain, when Judy Garland follows the yellow brick road, when Fred Astaire dances on the ceiling, when John Wayne puts the reins in his teeth and gallops across the mountain meadow, there is a purity and joy that cannot be resisted. In Equinox Flower, a Japanese film by the old master Yasujirō Ozu, there is this sequence of shots: A room with a red teapot in the foreground. Another view of the room. The mother folding clothes. A shot down a corridor with a mother crossing it at an angle, and then a daughter crossing at the back. A reverse shot in the hallway as the arriving father is greeted by the mother and daughter. A shot as the father leaves the frame, then the mother, then the daughter. A shot as the mother and father enter the room, as in the background the daughter picks up the red pot and leaves the frame. This sequence of timed movement and cutting is as perfect as any music ever written, any dance, any poem.[106]

Ebert credits film historian Donald Richie and the Hawaii International Film Festival for introducing him to Asian cinema through Richie's invitation to join him on the jury of the festival in 1983, which quickly became a favorite of his and would frequently attend along with Richie, lending their support to validate the festival's status as a "festival of record".[107][108] He lamented the decline of campus film societies: "There was once a time when young people made it their business to catch up on the best works by the best directors, but the death of film societies and repertory theaters put an end to that, and for today's younger filmgoers, these are not well-known names: Buñuel, Fellini, Bergman, Ford, Kurosawa, Ray, Renoir, Lean, Bresson, Wilder, Welles. Most people still know who Hitchcock was, I guess."[106]

Ebert argued for the aesthetic values of black-and-white photography and against colorization, writing:

Black-and-white movies present the deliberate absence of color. This makes them less realistic than color films (for the real world is in color). They are more dreamlike, more pure, composed of shapes and forms and movements and light and shadow. Color films can simply be illuminated. Black-and-white films have to be lighted ... Black and white is a legitimate and beautiful artistic choice in motion pictures, creating feelings and effects that cannot be obtained any other way.[109]

He wrote: "Black-and-white (or, more accurately, silver-and-white) creates a mysterious dream state, a simpler world of form and gesture. Most people do not agree with me. They like color and think a black-and-white film is missing something. Try this. If you have wedding photographs of your parents and grandparents, chances are your parents are in color and your grandparents are in black and white. Put the two photographs side by side and consider them honestly. Your grandparents look timeless. Your parents look goofy.

The next time you buy film for your camera, buy a roll of black-and-white. Go outside at dusk, when the daylight is diffused. Stand on the side of the house away from the sunset. Shoot some natural-light closeups of a friend. Have the pictures printed big, at least 5 x 7. Ask yourself if this friend, who has always looked ordinary in every color photograph you’ve ever taken, does not suddenly, in black and white, somehow take on an aura of mystery. The same thing happens in the movies."[106]

Ebert championed animation, particularly the films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.[110] In his review of Miyazaki's Princess Mononoke, he wrote: "I go to the movies for many reasons. Here is one of them. I want to see wondrous sights not available in the real world, in stories where myth and dreams are set free to play. Animation opens that possibility, because it is freed from gravity and the chains of the possible. Realistic films show the physical world; animation shows its essence. Animated films are not copies of 'real movies,' are not shadows of reality, but create a new existence in their own right."[111] He concluded his review of Ratatouille by writing: "Every time an animated film is successful, you have to read all over again about how animation isn't 'just for children' but 'for the whole family,' and 'even for adults going on their own.' No kidding!"[112]

Ebert championed documentaries, notably Errol Morris's Gates of Heaven: "They say you can make a great documentary about anything, as long as you see it well enough and truly, and this film proves it. Gates of Heaven, which has no connection to the unfortunate Heaven's Gate, is about a couple of pet cemeteries and their owners. It was filmed in Southern California, so of course we expect a sardonic look at the peculiarities of the Moonbeam State. But then Gates of Heaven grows ever so much more complex and frightening, until at the end it is about such large issues as love, immortality, failure, and the dogged elusiveness of the American Dream."[113] Morris credited Ebert's review with putting him on the map.[114] He championed Michael Apted's Up films, calling them "an inspired, even noble use of the medium."[115] Ebert concluded his review of Hoop Dreams by writing: "Many filmgoers are reluctant to see documentaries, for reasons I've never understood; the good ones are frequently more absorbing and entertaining than fiction. Hoop Dreams, however, is not only documentary. It is also poetry and prose, muckraking and expose, journalism and polemic. It is one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime."[116]

If a movie can illuminate the lives of other people who share this planet with us and show us not only how different they are but, how even so, they share the same dreams and hurts, then it deserves to be called great.

Ebert said that his favorite film was Citizen Kane, joking, "That's the official answer," although he preferred to emphasize it as "the most important" film. He said seeing The Third Man cemented his love of cinema: "This movie is on the altar of my love for the cinema. I saw it for the first time in a little fleabox of a theater on the Left Bank in Paris, in 1962, during my first $5 a day trip to Europe. It was so sad, so beautiful, so romantic, that it became at once a part of my own memories — as if it had happened to me."[118] He implied that his real favorite film was La Dolce Vita.[119]

His favorite actor was Robert Mitchum and his favorite actress was Ingrid Bergman.[120] He named Buster Keaton, Yasujirō Ozu, Robert Altman, Werner Herzog and Martin Scorsese as his favorite directors.[121] He expressed his distaste for "top-10" lists, and all movie lists in general, but did make an annual list of the year's best films, joking that film critics are "required by unwritten law" to do so. He also contributed an all-time top-10 list for the decennial Sight & Sound Critics' poll in 1982, 1992, 2002 and 2012. In 1982, he chose, alphabetically, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Bonnie and Clyde, Casablanca, Citizen Kane, La Dolce Vita, Notorious, Persona, Taxi Driver and The Third Man. In 2012, he chose 2001: A Space Odyssey, Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Apocalypse Now, Citizen Kane, La Dolce Vita, The General, Raging Bull, Tokyo Story, The Tree of Life and Vertigo.[122] Several of the contributors to Ebert's website participated in a video tribute to him, featuring films that made his Sight & Sound list in 1982 and 2012.[123]

Best films of the year

[edit]Ebert made annual "ten best lists" from 1967 to 2012.[124] His choices for best film of the year were:

- 1967: Bonnie and Clyde

- 1968: The Battle of Algiers

- 1969: Z

- 1970: Five Easy Pieces

- 1971: The Last Picture Show

- 1972: The Godfather

- 1973: Cries and Whispers

- 1974: Scenes from a Marriage

- 1975: Nashville

- 1976: Small Change

- 1977: 3 Women

- 1978: An Unmarried Woman

- 1979: Apocalypse Now

- 1980: The Black Stallion

- 1981: My Dinner with Andre

- 1982: Sophie's Choice

- 1983: The Right Stuff

- 1984: Amadeus

- 1985: The Color Purple

- 1986: Platoon

- 1987: House of Games

- 1988: Mississippi Burning

- 1989: Do the Right Thing

- 1990: Goodfellas

- 1991: JFK

- 1992: Malcolm X

- 1993: Schindler's List

- 1994: Hoop Dreams

- 1995: Leaving Las Vegas

- 1996: Fargo

- 1997: Eve's Bayou

- 1998: Dark City

- 1999: Being John Malkovich

- 2000: Almost Famous

- 2001: Monster's Ball

- 2002: Minority Report

- 2003: Monster

- 2004: Million Dollar Baby

- 2005: Crash

- 2006: Pan's Labyrinth

- 2007: Juno

- 2008: Synecdoche, New York

- 2009: The Hurt Locker

- 2010: The Social Network

- 2011: A Separation

- 2012: Argo

Ebert revisited and sometimes revised his opinions. After ranking E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial third on his 1982 list, it was the only movie from that year to appear on his later "Best Films of the 1980s" list (where it also ranked third).[125] He made similar reevaluations of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Ran (1985).[125] The Three Colours trilogy (Blue (1993), White (1994), and Red (also 1994), and Pulp Fiction (1994) originally ranked second and third on Ebert's 1994 list; both were included on his "Best Films of the 1990s" list, but their order had reversed.[126]

In 2006, Ebert noted his own "tendency to place what I now consider the year's best film in second place, perhaps because I was trying to make some kind of point with my top pick,"[127] adding, "In 1968, I should have ranked 2001 above The Battle of Algiers. In 1971, McCabe & Mrs. Miller was better than The Last Picture Show. In 1974, Chinatown was probably better, in a different way, than Scenes from a Marriage. In 1976, how could I rank Small Change above Taxi Driver? In 1978, I would put Days of Heaven above An Unmarried Woman. And in 1980, of course, Raging Bull was a better film than The Black Stallion ... although I later chose Raging Bull as the best film of the entire decade of the 1980s, it was only the second-best film of 1980 ... am I the same person I was in 1968, 1971, or 1980? I hope not."

Ebert's ten best lists resumed in 2014, the first full year after his death, as a Borda count system by his writers.

- 2014: Under the Skin

- 2015: Mad Max: Fury Road

- 2016: Moonlight

- 2017: Lady Bird

- 2018: Roma

- 2019: The Irishman

- 2020: Small Axe: Lovers Rock

- 2021: The Power of the Dog

- 2022: The Banshees of Inisherin

- 2023: [“Killers of the Flower Moon“]]

- 2024: The Brutalist

Best films of the decade

[edit]Ebert compiled "best of the decade" movie lists in the 2000s for the 1970s to the 2000s, thereby helping provide an overview of his critical preferences. Only three films for this listing were named by Ebert as the best film of the year, Five Easy Pieces (1970), Hoop Dreams (1994), and Synecdoche, New York (2008). In 2019, the editors of RogerEbert.com continued the tradition as a joint review of the RogerEbert.com writers.

- Five Easy Pieces (1970s)[128]

- Raging Bull (1980s)[129]

- Hoop Dreams (1990s)[130]

- Synecdoche, New York (2000s)[131]

- The Tree of Life (2010s) [132]

Genres and content

[edit]Ebert was often critical of the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system (MPAA). His main arguments were that they were too strict on sex and profanity, too lenient on violence, secretive with their guidelines, inconsistent in applying them and not willing to consider the wider context and meaning of the film.[133][134] He advocated replacing the NC-17 rating with separate ratings for pornographic and nonpornographic adult films.[133] He praised This Film is Not Yet Rated, a documentary critiquing the MPAA, adding that their rules are "Kafkaesque."[135] He signed off on his review of Almost Famous by asking, "Why did they give an R rating to a movie so perfect for teenagers?"[136]

Ebert also frequently lamented that cinemas outside major cities are "booked by computer from Hollywood with no regard for local tastes," making high-quality independent and foreign films virtually unavailable to most American moviegoers.[137]

He wrote that "I've always preferred generic approach to film criticism; I ask myself how good a movie is of its type."[138] He gave Halloween four stars: "Seeing it, I was reminded of the favorable review I gave a few years ago to Last House on the Left, another really terrifying thriller. Readers wrote to ask how I could possibly support such a movie. But I wasn't supporting it so much as describing it: You don't want to be scared? Don't see it. Credit must be paid to directors who want to really frighten us, to make a good thriller when quite possibly a bad one would have made as much money. Hitchcock is acknowledged as a master of suspense; it's hypocrisy to disapprove of other directors in the same genre who want to scare us too."[139]

Ebert did not believe in grading children's movies on a curve, as he thought children were smarter than given credit for and deserved quality entertainment. He began his review of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory: "Kids are not stupid. They are among the sharpest, cleverest, most eagle-eyed creatures on God's green Earth, and very little escapes their notice. You may not have observed that your neighbor is still using his snow-tires in mid-July, but every four-year-old on the block has, and kids pay the same attention when they go to the movies. They don't miss a thing, and have an instinctive contempt for shoddy and shabby work. I make this observation because nine out of ten kids' movies are stupid, witless and display contempt for their audiences. Is that all parents want from kids' movies? That they not have anything bad in them? Shouldn't they have something good in them — some life, imagination, fantasy, inventiveness, something to tickle the imagination? If a movie isn't going to do your kids any good, why let them watch it? Just to kill a Saturday afternoon? That shows a subtle contempt for a child's mind, I think." He went on to say he thought Willy Wonka was the best movie of its kind since The Wizard of Oz.[140]

Ebert tried not to judge a film on its ideology. Reviewing Apocalypse Now, he writes: "I am not particularly interested in the 'ideas' in Coppola's film...Like all great works of art about war, Apocalypse Now essentially contains only one idea or message, the not-especially-enlightening observation that war is hell. We do not go to see Coppola's movie for that insight — something Coppola, but not some of his critics, knows well. Coppola also well knows (and demonstrated in The Godfather films) that movies aren't especially good at dealing with abstract ideas — for those you'd be better off turning to the written word — but they are superb for presenting moods and feelings, the look of a battle, the expression on a face, the mood of a country. Apocalypse Now achieves greatness not by analyzing our 'experience in Vietnam,' but by re-creating, in characters and images, something of that experience."[141] Ebert commented on films using his Catholic upbringing as a point of reference,[11] and was critical of films he believed were grossly ignorant of or insulting to Catholicism, such as Stigmata (1999)[142] and Priest (1994).[143] He also gave favorable reviews of controversial films relating to Jesus Christ or Catholicism, including The Last Temptation of Christ (1988),[144] The Passion of the Christ (2004), and Kevin Smith's religious satire Dogma (1999).[145] He defended Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing: "Some of the advance articles about this movie have suggested that it is an incitement to racial violence. Those articles say more about their authors than about the movie. I believe that any good-hearted person, white or black, will come out of this movie with sympathy for all of the characters. Lee does not ask us to forgive them, or even to understand everything they do, but he wants us to identify with their fears and frustrations. Do the Right Thing doesn't ask its audiences to choose sides; it is scrupulously fair to both sides, in a story where it is our society itself that is not fair."[146]

Contrarian reviews

[edit]Metacritic later noted that Ebert tended to give more lenient ratings than most critics. His average film rating was 71%, if translated into a percentage, compared to 59% for the site as a whole. Of his reviews, 75% were positive and 75% of his ratings were better than his colleagues.[147] Ebert had acknowledged in 2008 that he gave higher ratings on average than other critics, though he said this was in part because he considered a rating of 3 out of 4 stars to be the general threshold for a film to get a "thumbs up."[148]

Writing in Hazlitt about Ebert's reviews, Will Sloan argued that "[t]here were inevitably movies where he veered from consensus, but he was not provocative or idiosyncratic by nature."[149] Examples of Ebert dissenting from other critics include his negative reviews of such celebrated films as Blue Velvet ("marred by sophomoric satire and cheap shots"),[150] A Clockwork Orange ("a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading as an Orwellian warning"),[151] and The Usual Suspects ("To the degree that I do understand, I don't care").[152] He gave only two out of four stars to the widely acclaimed Brazil, calling it "very hard to follow"[153] and is the only critic on RottenTomatoes to not like it.[154]

He gave a one-star review to the critically acclaimed Abbas Kiarostami film Taste of Cherry, which won the Palme d'Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival.[155] Ebert later added the film to a list of his most-hated movies of all time.[156] He was dismissive of the 1988 Bruce Willis action film Die Hard, stating that "inappropriate and wrongheaded interruptions reveal the fragile nature of the plot".[157] His positive 3 out of 4 stars review of 1997's Speed 2: Cruise Control, "Movies like this embrace goofiness with an almost sensual pleasure"[158] is one of only three positive reviews accounting for that film's 4% approval rating on the reviewer aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, one of the two others having been written by his At the Movies co-star Gene Siskel.[159]

Ebert reflected on his Speed 2 review in 2013, and wrote that it was "Frequently cited as an example of what a lousy critic I am," but defended his opinion, and noted, "I'm grateful to movies that show me what I haven't seen before, and Speed 2 had a cruise ship plowing right up the main street of a Caribbean village."[160] In 1999, Ebert held a contest for University of Colorado Boulder students to create short films with a Speed 3 theme about an object that could not stop moving.[160] The winning entrant was set on a roller coaster and was screened at Ebertfest that year.[160]

Other interests

[edit]In addition to film, Ebert occasionally wrote about other topics for the Sun-Times, such as music. In 1970, Ebert wrote the first published concert review of singer-songwriter John Prine, who at the time was working as a mailman and performing at Chicago folk clubs.[161]

Ebert was a lifelong reader, and said he had "more or less every book I have owned since I was seven, starting with Huckleberry Finn." Among the authors he considered indispensable were Shakespeare, Henry James, Willa Cather, Colette and Simenon.[162] He writes of his friend William Nack: "He approached literature like a gourmet. He relished it, savored it, inhaled it, and after memorizing it rolled it on his tongue and spoke it aloud. It was Nack who already knew in the early 1960s, when he was a very young man, that Nabokov was perhaps the supreme stylist of modern novelists. He recited to me from Lolita, and from Speak, Memory and Pnin. I was spellbound." Every time Ebert saw Nack, he'd ask him to recite the last lines of The Great Gatsby.[163] Reviewing Stone Reader, he wrote: "get me in conversation with another reader, and I'll recite titles, too. Have you ever read The Quincunx? The Raj Quartet? A Fine Balance? Ever heard of that most despairing of all travel books, The Saddest Pleasure, by Moritz Thomsen? Does anybody hold up better than Joseph Conrad and Willa Cather? Know any Yeats by heart? Surely P. G. Wodehouse is as great at what he does as Shakespeare was at what he did."[164] Among contemporary authors he admired Cormac McCarthy, and credited Suttree with reviving his love of reading after his illness.[165] He also loved audiobooks, particularly praising Sean Barrett's reading of Perfume.[166] He was a fan of Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin, which he read in French.[167]

Ebert first visited London in 1966 with his professor Daniel Curley, who "started me on a lifelong practice of wandering around London. From 1966 to 2006, I visited London never less than once a year and usually more than that. Walking the city became a part of my education, and in this way I learned a little about architecture, British watercolors, music, theater and above all people. I felt a freedom in London I've never felt elsewhere. I made lasting friends. The city lends itself to walking, can be intensely exciting at eye level, and is being eaten alive block by block by brutal corporate leg-lifting." Ebert and Curley coauthored The Perfect London Walk.[168]

Ebert attended the Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado Boulder for many years. It was there that he coined the Boulder Pledge: "Under no circumstances will I ever purchase anything offered to me as the result of an unsolicited e-mail message. Nor will I forward chain letters, petitions, mass mailings, or virus warnings to large numbers of others. This is my contribution to the survival of the online community."[169][170][171] Starting in 1975, he hosted a program called Cinema Interruptus, where would analyze a film with an audience, and anyone could say "Stop!" to point out anything they found interesting. He wrote "Boulder is my hometown in an alternate universe. I have walked its streets by day and night, in rain, snow, and sunshine. I have made life-long friends there. I was in my twenties when I first came to the Conference on World Affairs and was greeted by Howard Higman, its choleric founder, with 'Who invited you back?' Since then I have appeared on countless panels panels where I have learned and rehearsed debatemanship, the art of talking to anybody about anything." In 2009, Ebert invited Ramin Bahrani to join him in analyzing Bahrani's film Chop Shop a frame at a time. The next year, they invited Werner Herzog to join them in analyzing Aguirre, the Wrath of God. After that, Ebert announced that he would not return to the conference: "It is fueled by speech, and I'm out of gas ... But I went there for my adult lifetime and had a hell of a good time."[172]

Relations with filmmakers

[edit]Ebert wrote Martin Scorsese's first review, for Who's That Knocking at My Door, and predicted the director could be "an American Fellini someday."[37] He later wrote, "Of the directors who started making films since I came on the job, the best is Martin Scorsese. His camera is active, not passive. It doesn’t regard events, it participates in them. There is a sequence in GoodFellas that follows Henry Hill’s last day of freedom, before the cops swoop down. Scorsese uses an accelerating pacing and a paranoid camera that keeps looking around, and makes us feel what Hill feels. It is easy enough to make an audience feel basic emotions ('Play them like a piano,' Hitchcock advised), but hard to make them share a state of mind. Scorsese can do it."[106] In 2000, Scorsese joined Ebert on his show in choosing the best films of the 1990s.[55]

Ebert was an admirer of Werner Herzog, and conducted a Q&A session with him at the Walker Arts Center in 1999. It was there that Herzog read his "Minnesota Declaration" which defined his idea of "ecstatic truth."[173] Herzog dedicated his Encounters at the End of the World to Ebert, and Ebert responded with an open letter of gratitude.[174] Ebert often quoted something Herzog told him: "our civilization is starving for new images."[175]

When Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny (2003) premiered at Cannes, Ebert called it the worst film in the history of the festival. Gallo responded by putting a curse on his colon and a hex on his prostate. Ebert replied, "I had a colonoscopy once, and they let me watch it on TV. It was more entertaining than The Brown Bunny." Gallo called Ebert a "fat pig". Ebert replied: "It is true that I am fat, but one day I will be thin, and he will still be the director of The Brown Bunny."[176] Ebert gave the director's cut a positive review, writing that Gallo "is not the director of the same Brown Bunny I saw at Cannes, and the film now plays so differently that I suggest the original Cannes cut be included as part of the eventual DVD, so that viewers can see for themselves how 26 minutes of aggressively pointless and empty footage can sink a potentially successful film...Make no mistake: The Cannes version was a bad film, but now Gallo's editing has set free the good film inside."[177]

In 2005, Los Angeles Times critic Patrick Goldstein wrote that the year’s Best Picture Nominees were "ignored, unloved and turned down flat by most of the same studios that … bankroll hundreds of sequels, including a follow-up to Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo, a film that was sadly overlooked at Oscar time because apparently nobody had the foresight to invent a category for Best Running Penis Joke Delivered by a Third-Rate Comic." Rob Schneider responded in an open letter: "Well, Mr. Goldstein, I decided to do some research to find out what awards you have won. I went online and found that you have won nothing. Absolutely nothing. No journalistic awards of any kind … Maybe you didn’t win a Pulitzer Prize because they haven’t invented a category for Best Third-Rate, Unfunny Pompous Reporter Who’s Never Been Acknowledged by His Peers." Reviewing Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo, Ebert responded: "Reading this, I was about to observe that Schneider can dish it out but he can’t take it. Then I found he’s not so good at dishing it out, either. I went online and found that Patrick Goldstein has won a National Headliner Award, a Los Angeles Press Club Award, a RockCritics.com award, and the Publicists’ Guild award for lifetime achievement ... Schneider is correct, and Patrick Goldstein has not yet won a Pulitzer Prize. Therefore, Goldstein is not qualified to complain that Columbia financed Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo while passing on the opportunity to participate in Million Dollar Baby, Ray, The Aviator, Sideways and Finding Neverland. As chance would have it, I have won the Pulitzer Prize, and so I am qualified. Speaking in my official capacity as a Pulitzer Prize winner, Mr. Schneider, your movie sucks."[178] After Ebert's cancer surgery, he received a bouquet from "Your Least Favorite Movie Star, Rob Schneider". Ebert wrote of the flowers, "They were a reminder, if I needed one, that although Rob Schneider might (in my opinion) have made a bad movie, he is not a bad man, and no doubt tried to make a wonderful movie, and hopes to again. I hope so, too."[179]

Views on technology

[edit]Ebert was a strong advocate for Maxivision 48, in which the movie projector runs at 48 frames per second, as compared to the usual 24 frames per second. He was opposed to the practice whereby theaters lower the intensity of their projector bulbs in order to extend the life of the bulb, arguing that this has little effect other than to make the film harder to see.[180] Ebert was skeptical of the resurgence of 3D effects in film, which he found unrealistic and distracting.[181]

In 2005, Ebert opined that video games are not art, and are inferior to media created through authorial control, such as film and literature, stating, "video games can be elegant, subtle, sophisticated, challenging and visually wonderful," but "the nature of the medium prevents it from moving beyond craftsmanship to the stature of art."[182] This resulted in negative reaction from video game enthusiasts,[183] such as writer Clive Barker, who defended video games as an art form. Ebert wrote a further piece in response to Barker.[184] Ebert maintained his position in 2010, but conceded that he should not have expressed this skepticism without being more familiar with the actual experience of playing them. He admitted that he barely played video games: "I have played Cosmology of Kyoto which I enormously enjoyed, and Myst for which I lacked the patience."[185] In the article, Ebert wrote, "It is quite possible a game could someday be great art."[185]

Ebert had reviewed Cosmology of Kyoto for Wired in 1994, and had praised the exploration, depth, and graphics found in the game, writing "This is the most beguiling computer game I have encountered, a seamless blend of information, adventure, humor, and imagination — the gruesome side-by-side with the divine."[186] Ebert filed one other video game-related article for Wired in 1994, in which he described his visit to Sega's Joypolis arcade in Tokyo.[187]

Appearances in other media

[edit]Ebert provided DVD audio commentaries for Citizen Kane (1941), Casablanca (1942), Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) and Dark City (1998). For the Criterion Collection, he recorded commentaries for Floating Weeds (1959) and Crumb (1994), the latter with director Terry Zwigoff. Ebert was also interviewed by Central Park Media for an extra feature on the DVD release of Grave of the Fireflies (1988).

In 1982, 1983 and 1985, Gene Siskel and Ebert appeared as themselves on Saturday Night Live.[188][189] For their first two appearances, they reviewed sketches from that night's telecast; for their last, they reviewed sketches from the "SNL Film Festival".[190] In 1991, Siskel and Ebert appeared in the Sesame Street segment "Sneak Peek Previews" (a parody of Sneak Previews).[191] That year, the two were in the show's celebrity version of "Monster in the Mirror".[192] In 1995, Siskel and Ebert guest-starred on an episode of the animated sitcom The Critic. In the episode, a parody of Sleepless in Seattle, Siskel and Ebert split and each wants protagonist Jay Sherman, a fellow film critic, as his new partner.[193]

In 1997, Ebert appeared in Pitch, a documentary by Spencer Rice and Kenny Hotz[194] and the Chicago-set television series Early Edition,[195] where consoles a young boy who is depressed after he sees the character Bosco the Bunny die in a movie.[196] Ebert made a cameo in Abby Singer (2003).[197] In 2004, Ebert appeared in Sesame Street's direct-to-video special A Celebration of Me, Grover, delivering a review of the Monsterpiece Theater segment "The King and I".[198] Ebert was one of the principal critics featured in Gerald Peary's 2009 documentary For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism. He discusses the dynamics of appearing with Gene Siskel on the 1970s show Coming to a Theatre Near You, the predecessor of Sneak Previews on Chicago PBS station WTTW, and expresses approval of the proliferation of young people writing film reviews today on the internet.[199] On October 22, 2010, Ebert appeared with Robert Osborne on Turner Classic Movies during their "The Essentials" series. Ebert selected Sweet Smell of Success (1957) and The Lady Eve (1941).[200]

A "Mayor Ebert" (Michael Lerner) appeared in the 1998 remake of Godzilla. In his review, Ebert wrote: "Now that I've inspired a character in a Godzilla movie, all I really still desire is for several Ingmar Bergman characters to sit in a circle and read my reviews to one another in hushed tones."[201]

Personal life

[edit]

Marriage

[edit]At age 50, Ebert married trial attorney Charlie "Chaz" Hammel-Smith[202][203] in 1992.[11][204][205] Chaz Ebert became vice president of the Ebert Company and has emceed Ebertfest.[206][207][208] He explained in his memoir, Life Itself, that he did not want to marry before his mother died, as he was afraid of displeasing her.[209] In a July 2012 blog entry, Ebert wrote about Chaz, "She fills my horizon, she is the great fact of my life, she has my love, she saved me from the fate of living out my life alone, which is where I seemed to be heading... She has been with me in sickness and in health, certainly far more sickness than we could have anticipated. I will be with her, strengthened by her example. She continues to make my life possible, and her presence fills me with love and a deep security. That's what a marriage is for. Now I know."[210]

Alcoholism recovery

[edit]Ebert was a recovering alcoholic, having quit drinking in 1979. He was a member of Alcoholics Anonymous and had written some blog entries on the subject.[211] Ebert was a longtime friend of Oprah Winfrey, and Winfrey credited him with persuading her to syndicate The Oprah Winfrey Show,[212] which became the highest-rated talk show in American television history.[213]

Health

[edit]

In February 2002, Ebert was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer which was successfully removed.[214] In 2003, he underwent surgery for salivary gland cancer, which was followed up by radiation therapy. He was again diagnosed with cancer in 2006. In June of that year, he had a mandibulectomy to remove cancerous tissue in the right side of his jaw.[215] A week later he had a life-threatening complication when his carotid artery burst near the surgery site.[216] He was confined to bed rest and was unable to speak, eat, or drink for a time, necessitating the use of a feeding tube.[217]

The complications kept Ebert off the air for an extended period. Ebert made his first public appearance since mid-2006 at Ebertfest on April 25, 2007. He was unable to speak, instead communicating through his wife.[218] He returned to reviewing on May 18, 2007, when three of his reviews were published in print.[219] In July 2007, he revealed that he was still unable to speak.[220] Ebert adopted a computerized voice system to communicate, eventually using a copy of his own voice created from his recordings by CereProc.[221]

In March 2010, his health trials and new computerized voice were featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show.[222][223] In 2011, Ebert gave a TED talk assisted by his wife, Chaz, and friends Dean Ornish and John Hunter, called "Remaking my voice"[224] in which, he proposed a test to determine the verisimilitude of a synthesized voice.[225]

Ebert underwent further surgery in January 2008 to try to restore his voice and address the complications from his previous surgeries.[226][227] On April 1, Ebert announced his speech had not been restored.[228] Ebert underwent further surgery in April 2008 after fracturing his hip in a fall.[229] By 2011, Ebert had a prosthetic chin made to hide some of the damage done by his many surgeries.[230]

In December 2012, Ebert was hospitalized due to the fractured hip, which was subsequently determined to be the result of cancer.[231]

Ebert wrote that "what's sad about not eating" was:

The loss of dining, not the loss of food. It may be personal, but for me, unless I'm alone, it doesn't involve dinner if it doesn't involve talking. The food and drink I can do without easily. The jokes, gossip, laughs, arguments and shared memories I miss. Sentences beginning with the words, "Remember that time?" I ran in crowds where anyone was likely to break out in a poetry recitation at any time. Me too. But not me anymore. So yes, it's sad. Maybe that's why I enjoy this blog. You don't realize it, but we're at dinner right now.[232]

Politics

[edit]A supporter of the Democratic Party,[233] he wrote of how his Catholic schooling led him to his politics: "Through a mental process that has by now become almost instinctive, those nuns guided me into supporting universal health care, the rightness of labor unions, fair taxation, prudence in warfare, kindness in peacetime, help for the hungry and homeless, and equal opportunity for the races and genders. It continues to surprise me that many who consider themselves religious seem to tilt away from me."[234]

Ebert was critical of political correctness, "a rigid feeling that you have to keep your ideas and your ways of looking at things within very narrow boundaries, or you'll offend someone. Certainly one of the purposes of journalism is to challenge that kind of thinking. And certainly one of the purposes of criticism is to break boundaries. It's also one of the purposes of art."[235] He lamented that Adventures of Huckleberry Finn "has regrettably been under fire in recent years from myopic advocates of Political Correctness, who do not have a bone of irony (or humor) in their bodies, and cannot tell the difference between what is said or done in the novel, and what Twain means by it."[236] Ebert defended the cast and crew of Justin Lin's Better Luck Tomorrow (2002) during a Sundance Film Festival screening when a white member of the audience asked “Why, with the talent yup there and yourself, make a film so empty and amoral for Asian Americans and for Americans?” Ebert responded that "What I find very offensive and condescending about your statement is nobody would say to a bunch of white filmmakers, ‘How could you do this to 'your people'?...Asian-American characters have the right to be whoever the hell they want to be. They do not have to represent 'their people'!"[237][238][239] He was a supporter of the film after the incident at Sundance.

Ebert opposed the Iraq War, writing: "Am I against the war? Of course. Do I support our troops? Of course. They were sent to endanger their lives by zealots with occult objectives."[240] He endorsed Barack Obama for re-election in 2012, citing the Affordable Care Act as one important reason for his support of Obama.[241] He was concerned about income inequality, writing: "I have no objection to financial success. I've had a lot of it myself. All of my income came from paychecks from jobs I held and books I published. I have the quaint idea that wealth should be obtained by legal and conventional means–by working, in other words–and not through the manipulation of financial scams. You're familiar with the ways bad mortgages were urged upon people who couldn't afford them, by banks who didn't care that the loans were bad. The banks made the loans and turned a profit by selling them to investors while at the same time betting against them on their own account. While Wall Street was knowingly trading the worthless paper that led to the financial collapse of 2008, executives were being paid huge bonuses."[242] He voiced tentative support for the Occupy Wall Street movement: "I believe the Occupiers are opposed to the lawless and destructive greed in the financial industry, and the unhealthy spread in this country between the rich and the rest." Referring to the subprime mortgage crisis, he wrote: "I have also felt despair at the way financial instruments were created and manipulated to deliberately defraud the ordinary people in this country. At how home buyers were peddled mortgages they couldn't afford, and civilian investors were sold worthless 'securities' based on those bad mortgages. Wall Street felt no shame in backing paper that was intended to fail, and selling it to customers who trusted them. This is clear and documented. It is theft and fraud on a staggering scale."[243] He was also sympathetic to Ron Paul, noting that he "speaks directly and clearly without a lot of hot air and lip flap".[244] In a review of the 2008 documentary I.O.U.S.A., he credited Paul with being "a lonely voice talking about the debt", proposing based on the film that the US government was "already broke".[245] He opposed the war on drugs[246] and capital punishment.[247]

Laura Emerick, his Sun Times editor, recalled: “His union sympathies began at an early age. His father, Walter, worked as an electrician, and Roger remained a member of the Newspaper Guild throughout his career — though after he became an independent contractor, he probably could have opted out. He famously stood with the Guild in 2004, when he wrote to then publisher John Cruickshank that ‘it would be with a heavy heart that I would go on strike against my beloved Sun-Times, but strike I will if a strike is called.'”[248] He lamented that "Most Americans don’t understand the First Amendment, don’t understand the idea of freedom of speech, and don’t understand that it’s the responsibility of the citizen to speak out." Regarding his own freedom of speech, he said: "I write op-ed columns for the Chicago Sun-Times, and people send me e-mails saying, 'You're a movie critic. You don't know anything about politics.' Well, you know what, I'm 60 years old, and I've been interested in politics since I was on my daddy's knee.... I know a lot about politics."[249]

Beliefs

[edit]Ebert was critical of intelligent design,[250][251] and stated that people who believe in either creationism or New Age beliefs such as crystal healing or astrology should not be president.[252] He wrote that in Catholic school he learned of the "Theory of Evolution, which in its elegance and blinding obviousness became one of the pillars of my reasoning, explaining so many things in so many ways. It was an introduction not only to logic but to symbolism, thus opening a window into poetry, literature and the arts in general. All my life I have deplored those who interpret something only on its most simplistic level."[234]

Ebert described himself as an agnostic on at least one occasion,[11] but at other times explicitly rejected that designation; biographer Matt Singer wrote that Ebert opposed any categorization of his beliefs.[253] In 2009, Ebert wrote that he did not "want [his] convictions reduced to a word," and stated, "I have never said, although readers have freely informed me I am an atheist, an agnostic, or at the very least a secular humanist – which I am."[254] He wrote of his Catholic upbringing: "I believed in the basic Church teachings because I thought they were correct, not because God wanted me to. In my mind, in the way I interpret them, I still live by them today. Not by the rules and regulations, but by the principles. For example, in the matter of abortion, I am pro-choice, but my personal choice would be to have nothing to do with an abortion, certainly not of a child of my own. I believe in free will, and believe I have no right to tell anyone else what to do. Above all, the state does not." He wrote "I am not a believer, not an atheist, not an agnostic. I am still awake at night, asking how?[a] I am more content with the question than I would be with an answer."[254] He writes: "I was asked at lunch today who or what I worshiped. The question was asked sincerely, and in the same spirit I responded that I worshiped whatever there might be outside knowledge. I worship the void. The mystery. And the ability of our human minds to perceive an unanswerable mystery. To reduce such a thing to simplistic names is an insult to it, and to our intelligence."[255]

He wrote: "I drank for many years in a tavern that had a photograph of Brendan Behan on the wall, and under it is this quotation, which I memorized: 'I respect kindness in human beings first of all, and kindness to animals. I don't respect the law; I have a total irreverence for anything concerned with society except that which makes the roads safer, the beer stronger, the food cheaper and the old men and the old women warmer in the winter and happier in the summer.' For 57 words, that does a pretty good job of summing it up."[256] Summarizing his beliefs, Ebert wrote:

I believe that if, at the end of it all, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts. We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try. I didn't always know this, and am happy I lived long enough to find it out.[256]

He wrote: "I correspond with a dear friend, the wise and gentle Australian director Paul Cox. Our subject sometimes turns to death. In 2010 he came very close to dying before receiving a liver transplant. In 1988 he made a documentary named Vincent: The Life and Death of Vincent Van Gogh. Paul wrote that in his Arles days, van Gogh called himself 'a simple worshiper of the external Buddha.' Paul told me that in those days, Vincent wrote:

Looking at the stars always makes me dream, as simply as I dream over the black dots representing towns and villages on a map.

Why, I ask myself, shouldn't the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France?

Just as we take a train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star. We cannot get to a star any more when we are alive than we can take the train when we are dead. So to me it seems possible that cholera, tuberculosis and cancer are the celestial means of locomotion. Just as steamboats, buses and railways are the terrestrial means.

To die simply of old age would be to go there on foot.

That is a lovely thing to read, and a relief to find I will probably take the celestial locomotive. Or, as the little dog, Milou, says whenever Tintin proposes a journey, 'Not by foot, I hope!'"[257]

Death and legacy

[edit]On April 4, 2013, Ebert died at age 70 at a hospital in Chicago, shortly before he was set to return to his home and enter hospice care.[3][258][259][260]

President Barack Obama wrote, "For a generation of Americans — and especially Chicagoans — Roger was the movies... [he could capture] the unique power of the movies to take us somewhere magical. ... The movies won't be the same without Roger."[261] Martin Scorsese released a statement saying, "The death of Roger Ebert is an incalculable loss for movie culture and for film criticism. And it's a loss for me personally... there was a professional distance between us, but then I could talk to him much more freely than I could to other critics. Really, Roger was my friend. It's that simple."[262]

Steven Spielberg stated that Ebert's "reviews went far deeper than simply thumbs up or thumbs down. He wrote with passion through a real knowledge of film and film history, and in doing so, helped many movies find their audiences... [He] put television criticism on the map."[263] Numerous celebrities paid tribute including Christopher Nolan, Oprah Winfrey, Steve Martin, Albert Brooks, Jason Reitman, Ron Howard, Darren Aronofsky, Larry King, Cameron Crowe, Werner Herzog, Howard Stern, Steve Carell, Stephen Fry, Diablo Cody, Anna Kendrick, Jimmy Kimmel, and Patton Oswalt.[264]

Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune recalled that "I came late to film criticism in Chicago, after writing about the theater. Roger loved the theater. His was a theatrical personality: a raconteur, a spinner of dinner-table stories, a man who was not shy about his accomplishments. But he made room in that theatrical, improbable, outsized life for others."[265] Andrew O'Hehir of Salon wrote that "He's up there with Will Rogers, H. L. Mencken, A. J. Liebling and not too far short of Mark Twain as one of the great plainspoken commentators on American life."[266]

Peter Debruge wrote "Ebert’s negative reviews were invariably his most entertaining, and yet, he never insulted those who found something to admire in lesser films. Instead, he hoped to enlighten readers, challenging them to think, while whetting their appetite for stronger work ... It’s a testament to Ebert’s gift that, after a life spent writing about film, he made us love the movies all the more. ...I’ve always suspected the reason he settled into this profession is that film reviews, as he wrote them, served as a Trojan horse for the delivery of bigger philosophical ideas, of which he had an inexhaustible supply to share."[71]

"No one has done as much as Roger to connect the creators of movies with their consumers. He has immense power, and he’s used it for good, as an apostle of cinema. Reading his work, or listening to him parse the shots of some notable film, the movie lover is also engaged with an alert mind constantly discovering things — discovering them to share them. That’s what a great teacher does, and what Roger’s done as a writer, public personality and friend to film for all these years. And, dammit, keep on doing."