Brecon

Brecon

| |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Powys | |

| Population | 8,250 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SO045285 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Preserved county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BRECON |

| Postcode district | LD3 |

| Dialling code | 01874 |

| Police | Dyfed-Powys |

| Fire | Mid and West Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

| UK Parliament | |

| Senedd Cymru – Welsh Parliament | |

Brecon (/ˈbrɛkən/;[3] Welsh: Aberhonddu; pronounced [ˌabɛrˈhɔnði]),[citation needed] archaically known as Brecknock, is a market town in Powys, mid Wales. In 1841, it had a population of 5,701.[4] The population in 2001 was 7,901,[5] increasing to 8,250 at the 2011 census. Historically it was the county town of Brecknockshire (Breconshire); although its role as such was eclipsed with the formation of the County of Powys, it remains an important local centre. Brecon is the third-largest town in Powys, after Newtown and Ystradgynlais. It lies north of the Brecon Beacons mountain range, but is just within the Brecon Beacons National Park.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The Welsh name, Aberhonddu, means "mouth of the Honddu". It is derived from the River Honddu, which meets the River Usk near the town centre, a short distance away from the River Tarell which enters the Usk a few hundred metres upstream. After the Dark Ages the original Welsh name of the kingdom in whose territory Brecon stands was (in modern orthography) "Brycheiniog", which was later anglicised to Brecknock or Brecon, and probably derives from Brychan, the eponymous founder of the kingdom.[6]

Before the building of the bridge over the Usk, Brecon was one of the few places where the river could be forded. In Roman Britain Y Gaer (Cicucium) was established as a Roman cavalry base for the conquest of Roman Wales and Brecon was first established as a military base.[7]

Norman control

[edit]The confluence of the River Honddu and the River Usk made for a valuable defensive position for the Norman castle which overlooks the town, built by Bernard de Neufmarche in the late 11th century.[8]: 80 Gerald of Wales came and made some speeches in 1188 to recruit men to go to the Crusades.[9]

Town walls

[edit]Brecon's town walls were constructed by Humphrey de Bohun after 1240.[10]: 8 The walls were built of cobble, with four gatehouses and was protected by ten semi-circular bastions.[10]: 9 In 1400 the Welsh prince Owain Glyndŵr rose in rebellion against English rule, and in response in 1404, 100 marks was spent by the royal government improving the fortifications to protect Brecon in the event of a Welsh attack. Brecon's walls were largely destroyed during the English Civil War. Today only fragments survive, including some earthworks and parts of one of the gatehouses; these are protected as scheduled monuments.[11]

In Shakespeare's play King Richard III, the Duke of Buckingham is suspected of supporting the Welsh pretender Richmond (the future Henry VII), and declares:

O, let me think on Hastings and be gone

To Brecknock, while my fearful head is on![12]

Priory and cathedral

[edit]

A priory was dissolved in 1538, and Brecon's Dominican Friary of St Nicholas was suppressed in August of the same year.[13] About 250 m (270 yd) north of the castle stands Brecon Cathedral, a fairly modest building compared to many cathedrals. The role of cathedral is a fairly recent one, and was bestowed upon the church in 1923 with the formation of the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon from what was previously the archdeaconry of Brecon — a part of the Diocese of St Davids.[14]

St Mary's Church

[edit]Saint Mary's Church began as a chapel of ease to the priory but most of the building is dated to later medieval times. The West Tower, some 27 m (90 ft) high, was built in 1510 by Edward, Duke of Buckingham at a cost of £2,000. The tower has eight bells which have been rung since 1750, the heaviest of which weighs 810 kg (16 long hundredweight). They were cast by Rudhall of Gloucester. In March 2007 the bells were removed from the church tower for refurbishment. When the priory was elevated to the status of a cathedral, St Mary's became the parish church.[15][16] It is a Grade II* listed building.[17]

St David's Church, Llanfaes

[edit]

The Church of St David, referred to locally as Llanfaes Church, was probably founded in the early sixteenth century. The first parish priest, Maurice Thomas, was installed there by John Blaxton, Archdeacon of Brecon in 1555. The name is derived from the Welsh – Llandewi yn y Maes – which translates as 'St David's in the field'.[18]

Plough Lane Chapel, Lion Street

[edit]Plough Lane Chapel, also known as Plough United Reformed Church, is a Grade II* listed building. The present building dates back to 1841 and was re-modelled by Owen Morris Roberts.[19]

St Michael's Church

[edit]After the Reformation, some Breconshire families such as the Havards, the Gunters and the Powells persisted with Catholicism despite its suppression. In the 18th Century a Catholic Mass house in Watergate was active, and Rev John Williams was the local Catholic priest from 1788 to 1815. The present parish priest is Rev Father Jimmy Sebastian Pulickakunnel MCBS since 2012. The Watergate house was sold in 1805, becoming the current Watergate Baptist Chapel, and property purchased as the priest's residence and a chapel between Wheat Street and the current St Michael Street, including the "Three Cocks Inn"; about this time Catholic parish records began again. The normal round of bishop's visitations and confirmations resumed in the 1830s. In 1832 most civil liberties were restored to Catholics and they became able to practise their faith more openly. A simple Gothic church, dedicated to St Michael and designed by Charles Hansom, was built in 1851 at a cost of £1,000.[13]

Military town

[edit]The east end of town has two military establishments:

- Dering Lines, home to the Infantry Battle School (formerly Infantry Training Centre Wales)[20]

- The Barracks, Brecon, home to 160th (Wales) Brigade.[21]

Approximately 9 miles (14 km) to the west of Brecon is Sennybridge Training Area, an important training facility for the British Army.[22]

Geography

[edit]The town sits within the Usk valley at the point where the Honddu and Tarell rivers join it from north and south respectively. Two low hills overlook the town, the 331m high Pen-y-crug to its northwest and 231m high Slwch Tump to the east. Both are crowned by Iron Age hillforts. The modern administrative community includes the town of Brecon on the north bank of the Usk together with the smaller settlement of Llanfaes on its southern bank. Llanfaes is built largely on the floodplain of the Usk and the Tarell; embankments and walls protect parts of both Brecon and Llanfaes from this risk.[23]

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Brecon, at community (town) and county level: Brecon Town Council and Powys County Council. The town council is based at Brecon Guildhall on the High Street.[24]

The town council elects a mayor annually. In May 2018 it elected its first mixed race mayor, local hotelier Emmanuel (Manny) Trailor.[25]

Controversy

[edit]In 2010 the Town Council installed a plaque to the slave-trader Captain Thomas Phillips captain of the Hannibal slave ship.[26] During the worldwide Black Lives Matter protests the plaque was removed and thrown into the River Usk.[citation needed][27] Following the protests the Council passed two resolutions on 20 September 2020 to display the plaque in the local museum, Y Gaer, and to request that it is displayed as part of a suitable exhibit detailing the wider context, without being restored. It was also resolved unanimously that a working group is established to consider whether a new plaque, new work of art, or loaned artwork should be commissioned, and where any new piece should be located. [28]

Administrative history

[edit]Brecon was an ancient borough. Its date of becoming a borough is unknown, but it was described as having burgesses in 1100 and its first known charter was issued in 1276.[29] Until 1536, the town formed part of the wider Lordship of Brecknock, a marcher lordship. In 1536 the new county of Brecknockshire was created, with Brecon as its county town.[30]

The borough of Brecon's responsibilities were originally primarily judicial, holding various courts. The borough council also owned the manorial rights to the borough, oversaw the town's market and fairs, and ran elections for the borough's member of parliament. In 1776 a separate body of improvement commissioners was established to supply the town with water and pave and light the streets.[31]

The borough was reformed to become a municipal borough in 1836 under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which standarised how most boroughs operated across the country.[32] The improvement commissioners were abolished in 1850 when their functions were taken over by the borough council.[33][34]

The borough was abolished in 1974, with its area instead becoming a community called Brecon within the larger Borough of Brecknock in the new county of Powys. The former borough council's functions therefore passed to Brecknock Borough Council, which was in turn abolished in 1996 and its functions passed to Powys County Council.[35][36]

Education

[edit]

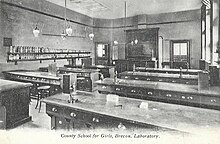

Brecon has primary schools, with a secondary school and further education college (Brecon Beacons College) on the northern edge of the town. The secondary school, known as Brecon High School, was formed from separate boys' and girls' grammar schools ('county schools') and Brecon Secondary Modern School, after comprehensive education was introduced into Breconshire in the early 1970s. The town is home to an independent school, Christ College, which was founded in 1541.[37]

Transport

[edit]

The junction of the east–west A40 (London-Monmouth-Carmarthen-Fishguard) and the north–south A470 (Cardiff-Merthyr Tydfil-Llandudno) is on the east side of Brecon town centre. The nearest airport is Cardiff Airport.[38]

The town's primary public transport hub is the Brecon Interchange at the B4601 Heol Gouesnou, served mainly by the long-distance T4, T6 and T14 routes operated by TrawsCymru. Local services 40A and 40B, operated by Stagecoach South Wales, connect the town centre with the suburbs, operating at a roughly-hourly frequency.[39]

Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal

[edit]The Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal runs for 35 miles (56 km) between Brecon and Pontnewydd, Cwmbran. It then continues to Newport, the towpath being the line of communication and the canal being disjointed by obstructions and road crossings. The canal was built between 1797 and 1812 to link Brecon with Newport and the Severn Estuary. The canalside in Brecon was redeveloped in the 1990s and is now the site of two mooring basins and Theatr Brycheiniog.[40]

Usk bridge

[edit]

The bridge carries the B4601 across the River Usk. A plaque on a house wall adjacent to the eastern end of the bridge records that the present bridge was built in 1563 to replace a medieval bridge destroyed by floods in 1535. It was repaired in 1772 and widened in 1794 by Thomas Edwards, the son of William Edwards of Eglwysilan. It had stone parapets until the 1970s when the present deck was superimposed on the old structure. The bridge was painted by J. M. W. Turner c.1769.[41]

Former railways

[edit]The Neath and Brecon Railway reached Brecon in 1867, terminating at Free Street. By this point, Brecon already had two other railway stations:

- Watton – from 1 May 1863 when the Brecon and Merthyr Railway to Merthyr Tydfil was opened for traffic[42]

- Mount Street – in September 1864, with Llanidloes by the Mid Wales Railway which linked to the Midland Railway at Talyllyn Junction. The three companies consolidated their stations at a newly rebuilt Free Street Joint Station from 1871[43] and the station finally closed in 1872[44]

Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway

[edit]

The Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway was opened gradually from Hereford towards Brecon. The first section opened in 1862, with passenger services on the complete line starting on 21 September 1864.[45] The Midland Railway Company (MR) took over the HH&BR from 1 October 1869, leasing the line by an Act of 30 July 1874 and absorbing the HH&BR in 1876.[46] The MR was absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) on 1 January 1923.[47]

Passenger services to Merthyr ended in 1958, Neath in October 1962 and Newport in December 1962. In 1962 the important line to Hereford closed. Therefore, Brecon lost all its train services before the 1963 Reshaping of British Railways report (often referred to as the Beeching Axe) was implemented.[48]

Culture

[edit]Brecon hosted the National Eisteddfod in 1889.[49]

August sees the annual Brecon Jazz Festival. Concerts are held in both open air and indoor venues, including the town's market hall and the 400-seat Theatr Brycheiniog, which opened in 1997.[40]

October sees the annual 4-day weekend Brecon Baroque Music Festival, organised by leading violinist Rachel Podger.[50]

Idris Davies put "the pink bells of Brecon" in his poem published as XV in Gwalia Deserta (by T. S. Eliot). This was copied in "Quite Early One Morning" by Dylan Thomas, put to music by Pete Seeger as the song "The Bells of Rhymney", then recorded by the Byrds where it became known to millions although by then the Brecon line had gone missing.[51]

Points of interest

[edit]

- Brecon Castle

- Brecon Beacons and National Park Visitor Centre (also known as the Mountain Centre)

- Brecon Beacons Food Festival

- Brecon Cathedral, the seat of the Diocese of Swansea and Brecon

- Brecon Jazz Festival

- Christ College, Brecon

- Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh

- Theatr Brycheiniog (Brecon Theatre)

- Y Gaer

Notable people

[edit]

- Sibyl de Neufmarché (ca.1100 – after 1143), Countess of Hereford, suo jure Lady of Brecknock

- Gerald of Wales (ca.1146 – ca.1223), a Cambro-Norman priest and historian.

- William de Braose (ca.1197 – 1230), a Marcher lord.[52]

- Dafydd Gam (ca.1380 – 1415), archer, died fighting for Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt

- Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (1478–1521) an English nobleman.

- Hugh Price (ca.1495 – 1574), founder of Jesus College, Oxford

- Admiral Sir William Wynter (ca.1521 – 1589), principal officer of the Council of the Marine

- Henry Vaughan (1621–1695), physician and author, a major Metaphysical poets.[53]

- John Jeffreys (ca.1623 - 1689), landowner and politician, first master of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham

- Captain Thomas Phillips[54] (late 17th century), commander of the Hannibal slave ship

- Thomas Coke (1747–1814), Mayor of Brecon in 1772 and the first Methodist bishop.[55]

- Sarah Siddons (1755–1831), tragedienne actress.[56]

- David Price (1762–1835), orientalist and officer in the East India Company.

- Charles Kemble (1775–1854), actor, younger brother of Sarah Siddons.[57]

- John Evan Thomas (1810–1873), a Welsh sculptor

- Mordecai Jones (1813-1880), businessman, pioneered the South Wales coalfield, Mayor of Brecon in 1854.

- Frances Hoggan (1843–1927), first British woman to receive a doctorate in medicine

- Ernest Howard Griffiths (1851–1932), physicist and academic

- Llewela Davies (1871–1952), pianist and composer

- Dame Olive Wheeler (1886–1963), educationist, psychologist and university lecturer

- Captain Richard Mayberry (1895–1917), World War I flying ace

- Lt Col S. F. Newcombe (1878–1956), Army Officer and associate of T. E. Lawrence.

- Tudor Watkins, Baron Watkins (1903–1983), politician and MP

- John Fullard (1907–1973), tenor singer with the Covent Garden Opera

- George Melly (1926–2007), trad jazz singer, art critic and writer, retreat at Brecon between 1971 and 1999

- Gareth Gwenlan (1937–2016), TV producer, director and executive

- Roger Glover (born 1945), bassist and songwriter with the band Deep Purple

- Jeb Loy Nichols (born ca.1965), musician

- Nia Roberts (born 1972), actress

- Gerard Cousins (born 1974), guitarist, composer and arranger.

- Natasha Marsh (born 1975), soprano singer.

- Sian Reese-Williams (born 1981), actress

Sport

[edit]- Frederick Bowley (1873–1943), a first-class cricketer for Worcestershire

- Walley Barnes (1920–1975), footballer with 299 club caps and 22 for Wales and a broadcaster.

- Adrian Street (1940-2023), a Welsh professional wrestler

- Andy Powell (born 1981), Welsh Rugby Union international number eight

- Sam Hobbs (born 1988), rugby union player with Cardiff Blues

- Jessica Allen (born 1989), a Welsh racing cyclist.

- Emma Plewa (born 1990), footballer with 20 caps with Wales women

Town twinning

[edit]Brecon is twinned with:

- Saline, Michigan, United States

- Blaubeuren, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. (Blaubeuren is twinned with Brecknockshire, which is an area of Powys, rather than with the town of Brecon.)

- Gouesnou, Brittany, France

- Dhampus, Kaski District, Nepal

References

[edit]- ^ "Town population 2011". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Brecon Town Council". Brecon Town Council. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Brecon". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol III, (1847) London, Charles Knight, p.765.

- ^ "Parish Headcounts: Powys", Census, Office for National Statistics, 2001, archived from the original on 13 June 2011, retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ "Brychan Brycheiniog, King of Brycheiniog". Early English Kingdoms. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "A short guide to Brecon Gaer Roman Fort". Clwyd Powys Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Davies (2008).

- ^ "Gerald's Journey through Wales in 1188". History Points. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b Pettifer (2000).

- ^ Davis, Philip, "Brecon Town Walls", Gatehouse, retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Cornwall, Barry (1853). The Plays of Shakspere, Carefully Revised from the Best Authorities. Vol. 2. p. 1250.

- ^ a b "History of St. Michael's Church – St. Michael's Catholic Church, Brecon". stmichaelsrcbrecon.org.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Swansea and Brecon". Crockford's Clerical Directory. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Bellringing". St Mary's Church in Wales. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "History". St Mary's Church Brecon. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Cadw. "Church of St Mary, Brecon, Powys (Grade II*) (7015)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Poole, Edwin (1886). The Illustrated History and Biography of Brecknockshire: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Illustrated by Several Engravings and Portraits (Public domain ed.). Edwin Poole. p. 67.

- ^ Cadw. "Plough Lane Chapel, Brecon (6945)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Brecon", Brigade of Gurkhas, UK: Army, archived from the original on 18 November 2004.

- ^ "Summary of Future Reserves 2020 (FR20) implementation measures within Wales" (PDF). Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "160the Wales Brigade", 5th Division, UK: Army[permanent dead link].

- ^ Barclay, W.J.; Davies, J.R.; Humpage, A.J.; Waters, R.A.; Wilby, P.R.; Williams, M.; Wilson, D. (2005). Geology of the Brecon District. Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey. p. 31. ISBN 0-85272-511-6.

- ^ "Brecon Town Council". Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "First mixed-race mayor elected by Brecon Town Council". The Brecon & Radnor Express. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Brecon & Radnor Express, 11 June 2020.https://www.brecon-radnor.co.uk/news/controversial-plaque-commemorating-brecons-links-to-slave-trader-is-removed-ahead-of-review-82586

- ^ Thomas, James (12 June 2020). "Slave trader's town centre plaque stripped from wall in Brecon". Hereford Times. p. 1.

- ^ https://brecontowncouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/DRAFT-Council-Minutes-28-September-2020.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Brecon Boroughs". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Laws in Wales Act 1535. 1536. p. 246. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Municipal Corporations in England and Wales: Appendix 1. 1835. pp. 177–184. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Municpal Corporations Act. 1835. p. 459. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Lawes, Edward (1851). The Act for Promoting the Public Health, with notes. London: Shaw and Sons. pp. 260–261. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Brecon Urban District / Municipal Borough". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972

- ^ Local Government (Wales) Act 1994

- ^ "Christ College Brecon in £5m anniversary investment boost". BBC News. BBC. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Getting There". Brecon Beacons. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "40A, 40B - Brecon - Brecon".

- ^ a b "Theatr Brycheiniog - The Theatres Trust". theatrestrust.org.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "Joseph Mallord William TurnerBrecon Bridge c.1798-9". Tate. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Barrie, D.S.M. (1980) [1957]. The Brecon and Merthyr Railway. Trowbridge: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-087-8.

- ^ "Railway stations", Victorian Brecon, UK: Powys

- ^ Railway Passenger Stations by M.Quick page 96

- ^ Butt 1995, p. 103

- ^ Awdry 1990, p. 80

- ^ Railways Act 1921, HMSO, 19 August 1921

- ^ Garry Keenor. "The Reshaping of British Railways – Part 1: Report". The Railways Archive. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Past locations". National Eisteddfod. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Brecon Baroque Music Festival". Music at Oxford. 21 October 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "The Bells of Rhymney". Welsh Not. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 432.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 955.

- ^ Caldicott, Rosemary L (1 March 2024). Voyage of Despair. The Hannibal, its captain and all who sailed in her, 1693-1695 (1st ed.). Bristol: Bristol Radical History Group. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-911522-63-8. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 655.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 37–38.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 723–724, see page 724.

Charles Kemble (1775–1854), a younger brother of....

Bibliography

[edit]- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 1-8526-0049-7. OCLC 19514063. CN 8983.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Caldicott, R. L. (2024). Voyage of Despair. The Hannibal, its captain and all who sailed in her, 1693-1695. BRHG Books. ISBN 978-1-911522-63-8

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Pettifer, Adrian (2000). Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-778-8.

External links

[edit] Brecon travel guide from Wikivoyage

Brecon travel guide from Wikivoyage- Brecon Town Council website