Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

| "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" | |

|---|---|

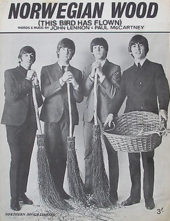

Cover of the song's sheet music | |

| Song by the Beatles | |

| from the album Rubber Soul | |

| Released | 3 December 1965 |

| Recorded | 21 October 1965 |

| Studio | EMI, London |

| Genre | |

| Length | 2:05 |

| Label | Parlophone |

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney |

| Producer(s) | George Martin |

| Audio sample | |

"Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", otherwise known as simply "Norwegian Wood", is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1965 album Rubber Soul. It was written mainly by John Lennon, with lyrical contributions from Paul McCartney, and credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership. Influenced by the introspective lyrics of Bob Dylan, especially the folk waltz style of "To Ramona", the song is considered a milestone in the Beatles' development as songwriters. The track features a sitar part, played by lead guitarist George Harrison, that marked the first appearance of the Indian string instrument on a Western rock recording. The song was a number 1 hit in Australia when released on a single there in 1966, coupled with "Nowhere Man".

Lennon wrote the song as a veiled account of an extramarital affair he had in London. When recording the track, Harrison was asked by Lennon to add a sitar part to the song.[5] Harrison had become interested in the instrument's exotic sound while on the set of the Beatles' film Help!, in early 1965. "Norwegian Wood" was influential in the development of raga rock and psychedelic rock during the mid-1960s. The song also helped elevate Ravi Shankar and Indian classical music to mainstream popularity in the West. Many other rock and pop artists, including the Byrds, the Rolling Stones and Donovan, began integrating elements of the genre into their musical approach. "Norwegian Wood" is also recognised as a key work in the early evolution of world music.

Rolling Stone magazine ranked "Norwegian Wood" number 83 on its 2004 list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[6]

Background and composition

[edit]The song's lyrics are about an extramarital affair that John Lennon was involved in, as hinted in the opening couplet: "I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me." Although Lennon never revealed with whom he had the affair, writer Philip Norman speculates that it was either Lennon's close friend and journalist Maureen Cleave or Sonny Freeman.[7] Paul McCartney explained that the term "Norwegian Wood" was an ironic reference to the cheap pine wall panelling then in vogue in London.[8] McCartney commented on the final verse of the song: "In our world the guy had to have some sort of revenge. It could have meant I lit a fire to keep myself warm, and wasn't the decor of her house wonderful? But it didn't, it meant I burned the fucking place down as an act of revenge, and then we left it there and went into the instrumental."[9]

According to Lennon in 1970, "Norwegian Wood" was his creation, with McCartney assisting on the middle eight.[10] In 1980, Lennon changed his claim, saying it was "my song completely".[10] Since Lennon's death, however, McCartney has contended that Lennon brought the opening couplet to one of their joint songwriting sessions, and that they finished the song together, with the middle eight and the title (and the "fire") being among McCartney's contributions.[9][10] McCartney's statement about the level of his involvement was one of the controversial claims he made in his 1997 authorised biography, Many Years from Now.[11]

Regardless, Lennon began writing the song in January 1965, while on holiday with his wife, Cynthia, and record producer George Martin at St. Moritz in the Swiss Alps.[12] Over the following days, Lennon expanded on an acoustic arrangement of the song, which was written in a Dylanesque 6

8 time signature, and showed it to Martin while he recovered from a skiing injury.[13][14] In his book The Songs of Lennon: The Beatle Years, author John Stevens describes "Norwegian Wood" as a turning point in folk-style ballads, writing that "Lennon moves quickly from one lyrical image to another, leaving it up to the listener's imagination to complete the picture". He also said the song marked a pivotal moment in Lennon's use of surreal lyrics, following on from the songs "Ask Me Why" and "There's a Place".[15]

Sitar and Indian influence

[edit]Between 5 and 6 April 1965, while filming the second Beatles film, Help!, at Twickenham Film Studios, George Harrison first encountered a sitar, the Indian string instrument that would be a prominent feature in "Norwegian Wood".[16] It was one of several instruments being played by a group of Indian musicians in a scene set in an Indian restaurant.[17][a]

"Norwegian Wood" was not the first Western pop song in which an Indian influence was evident: the raga-like drone was found in the Beatles' "Ticket to Ride",[20][21] as well as in the Kinks' song "See My Friends".[22][23] The Yardbirds also created a similar sound with a distorted electric guitar on "Heart Full of Soul".[22][23] Barry Fantoni, a friend of Ray Davies of the Kinks, said that the Beatles first got the idea to use Indian instrumentation when Fantoni played them "See My Friends".[24] According to author Ian MacDonald, however, while the Kinks' single most likely influenced the Beatles, Davies could well have been influenced by "Ticket to Ride" when recording "See My Friends".[24]

Rather than the Kinks or the Yardbirds, Harrison attributed his growing interest in Indian sounds to people mentioning the name of Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar to him, culminating in a discussion he had with David Crosby of the Byrds.[25] The discussion took place in Los Angeles on 25 August, during the Beatles' 1965 American tour.[26] Once back in London, Harrison followed Crosby's suggestion by seeking out Shankar's recordings,[27][28] and he also purchased a cheap sitar, from the Indiacraft store on Oxford Street.[29][30] Ringo Starr later cited Harrison's use of sitar on "Norwegian Wood" as an example of the Beatles' eagerness to incorporate new sounds in 1965, saying: "you could walk in with an elephant, as long as it was going to make a musical note."[31]

Recording

[edit]The Beatles recorded an early version of "Norwegian Wood" during the first day of sessions for their album Rubber Soul, on 12 October 1965.[32][33] The session took place at EMI Studios in London, with Martin producing.[34] Titled "This Bird Has Flown", the song was extensively rehearsed by the group, who then taped the rhythm track in a single take,[34] featuring two 12-string acoustic guitars, bass, and a faint sound of cymbals. At Lennon's behest, Harrison added his sitar part, with the take emphasising the drone quality of the instrument more so than the remake that was eventually released.[35] The sound of the sitar proved difficult to capture, according to sound engineer Norman Smith, who recalled problems with "a lot of nasty peaks and a very complex wave form". He declined to use a limiter, which would have fixed the technical problem with distortion, but would have affected the sound.[36]

Lennon overdubbed a lead vocal, which he double tracked at the end of each line in the verses. This version exhibited a less folk-orientated sound, relative to the recording issued on Rubber Soul, instead highlighting laboured vocals and an unusual sitar conclusion. The band were unsatisfied with the recording, however, and decided to return to the song later in the sessions.[37] This discarded version of "Norwegian Wood" was first released on the 1996 compilation album Anthology 2.[38]

On 21 October, the Beatles recorded three new takes, including the master.[39] The group experimented with the arrangement, with the second take introducing a double-tracked sitar opening that complemented Lennon's acoustic melody. Though the group completely reshaped "Norwegian Wood", it was far from the album version.[40] Harrison's sitar playing is still at the forefront, alongside heavy drumbeats. The take was not considered suitable for overdubbing, so the band scrapped it, and re-evaluated the arrangement.[37] By the third take, the song was called "Norwegian Wood", and the group changed the key from D major to E major.[b] The Beatles skipped the rhythm section on this take, and decided to jump directly to the master take.[42] In all, the rhythm section accommodates the acoustics, and the band thought the musical style was an improvement over earlier run-throughs. Therefore, the sitar is an accompaniment, consequently affecting the droning sound evident in past takes.[43] Looking back on the recording sessions in the 1990s, Harrison explained his inclusion of the sitar to be "quite spontaneous from what I remember", adding, "We miked it up and put it on and it just seemed to hit the spot".[44]

Release and reception

[edit]"Norwegian Wood" was released on Rubber Soul on 3 December 1965.[45][46][47] The song marked the first example of a rock band playing a sitar[48] or any Indian instrument on one of their recordings.[49] It was also issued on a single with "Nowhere Man" in Australia and was a number 1 hit there in May 1966.[50][51] The two songs were listed together, as a double A-side, during the single's two weeks at number 1.[52] In the United Kingdom, the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) awarded the song a silver certification for sales and streams exceeding 200,000 units in 2021.[53]

Writing for AllMusic, music historian Richie Unterberger describes "Norwegian Wood" as possessing "more than enough ambiguity and ingenious innuendo to satisfy even a Dylan fan" while demonstrating to the Beatles' audience how "the group had sure come a long way since 'She Loves You' just two years back." Unterberger concludes his review by commenting: "The power of the track is greatly enhanced by McCartney's sympathetic high harmonies on the bridge, and its exoticism confirmed by George Harrison's twanging sitar riffs".[54] A reviewer for Rolling Stone magazine noted "Norwegian Wood" and "Think for Yourself" as documents of the Beatles' increasing awareness and creativity in the studio.[55] Scott Plagenhoef of Pitchfork considers the song to be one of the most self-evident Lennon pieces on Rubber Soul to exemplify his maturity as a songwriter, and praises the composition as "an economical and ambiguous story-song highlighted by Harrison's first dabbling with the Indian sitar".[56]

In his book on the Rubber Soul era, subtitled The Enduring Beauty of Rubber Soul, John Kruth refers to "Norwegian Wood" as a "striking from the first listen" kind of tune that "transported Beatles fans north to the pristine forests of Scandinavia".[57] Music critic Kenneth Womack admires how the song "reinterprets a familiar theme, in this case the loss of 'love' (well represented in earlier songs such as 'Don't Bother Me' and 'Misery'), providing listeners with security yet challenging those inclined to acknowledge the standard treatment".[58]

Musical influence and legacy

[edit]Although droning guitars had been used previously to mimic the qualities of the sitar, "Norwegian Wood" is generally credited as sparking a musical craze for the sound of the novel instrument in the mid-1960s. The song is often identified as the first example of raga rock,[59] while the trend it initiated led to the arrival of Indian rock and formed the essence of psychedelic rock.[60][61] "Norwegian Wood" is also recognised as an important piece of what is typically called "world music", and it was a major step towards incorporating non-Western musical influences into Western popular music.[60][62] The composition, coupled with advice given by Harrison, sparked the interest of Rolling Stones multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones, who soon integrated the sitar into "Paint It Black", another landmark song in the development of raga and Indian rock.[63] Other pieces exemplifying the rapid growth of interest in Indian music by contemporary Western musicians include Donovan's "Sunshine Superman", the Yardbirds' "Shapes of Things" and the Byrds' "Eight Miles High", among others.[64]

According to author Jonathan Gould, the impact of "Norwegian Wood" "transformed" Ravi Shankar's career, and the Indian sitarist later wrote of first being aware of a "great sitar explosion" in popular music during the spring of 1966, when he was performing a series of concerts in the UK.[65] Harrison developed a fascination for Indian culture and mysticism, introducing it to the other Beatles. In June 1966, Harrison met Shankar in London and became a student under the master sitarist.[66] Having added the sitar accompaniment to "Norwegian Wood", Harrison expanded upon his initial effort by writing "Love You To", which showcased his immersion in Indian music, and presented an authentic representation of a non-Western music form in a rock song.[67][68] Before the recording sessions for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Harrison made a pilgrimage to Bombay, India with his wife Pattie, where he continued his studies with Shankar and was introduced to the teachings of several yogis.[69][70] Harrison contributed "Within You Without You" to Sgt. Pepper, featuring himself as the only performing Beatle together with uncredited musicians playing dilruba, swarmandal and tabla, alongside a string section.[71] For the remainder of his career, he evolved his understanding of Indian musicianship, particularly in his slide guitar playing.[72]

In 2006, Mojo placed "Norwegian Wood" at number 19 in the magazine's list of "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs", as compiled by a panel of music critics and musicians. In their commentary on the song, Roy Harper and John Cale both identified the track as an influence on their musical careers during the 1960s.[73] Harper wrote:

We all knew that they were good ... What you weren't prepared for was Rubber Soul. They were writing with a deeper resonance, in another time zone ... I was envious and inspired at the same moment. They'd come onto my turf, got there before me, and they were kings of it, overnight. We'd all been outflanked. The best song on the record was one of the shortest, Norwegian Wood. Tears came to my eyes, I wished I'd written it. The music was sublimely different. George's sitar was a well-placed act of fusion and the song was full of Lennon wit. After a few times on the turntable, you realised that the goal posts had been moved, forever, and you really wanted to hear the next record – now.[73]

Cale recalled that Rubber Soul was an inspiration to him and Lou Reed as they developed their band the Velvet Underground. He described the song's mood as "very acid ... what you remember in a flashback is a sound, how your senses were bombarded", adding: "I don't think anybody got that sound or that closeted feeling as well as The Beatles did on Norwegian Wood."[73] In his book The Beatles Through Headphones, Ted Montgomery comments: "Perhaps no other song in rock and roll history captures a feel and nuance more succinctly and powerfully in 2:05 than 'Norwegian Wood'."[74]

The song has been covered by numerous artists, including Waylon Jennings, Tangerine Dream, Cilla Black, Hank Williams Jr, Cornershop, The Fiery Furnaces, Rahul Dev Burman, Buddy Rich, P.M. Dawn[75][76] and Heather Nova. The Chemical Brothers sampled "Norwegian Wood" in their 1997 song "The Private Psychedelic Reel". In 1968, Alan Copeland won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Performance by a Chorus for a medley of "Norwegian Wood" and the theme from Mission: Impossible.[77]

Personnel

[edit]Personnel per Walter Everett[78]

- John Lennon – double-tracked vocals, acoustic guitar

- Paul McCartney – bass guitar, harmony vocals

- George Harrison – 12-string acoustic guitar, double-tracked sitar

- Ringo Starr – tambourine, bass drum, maracas, finger cymbals

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[79] | Silver | 200,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The musical score for Help! included an instrumental titled "Another Hard Day's Night". Scored by Martin, it was a medley of three Beatles compositions – "A Hard Day's Night", "Can't Buy Me Love" and "I Should Have Known Better" – arranged to feature the sitar, among other instruments.[18][19]

- ^ Because the song is structured around the D major chord, the re-make was probably recorded with a capo on the guitars, or sped up in the final mix.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Great Moments in Folk Rock: Lists of Author Favorites". richieunterberger.com. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Decker 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Church 2019, p. 130.

- ^ "The Rolling Stone Interview". John Lennon. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Norwegian Wood ranked 83rd greatest song". Rolling Stone. 11 December 2003. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Norman 2008, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Jackson 2015, pp. 257.

- ^ a b Miles 1997, pp. 270–71.

- ^ a b c "100 Greatest Beatles Songs". Rolling Stone. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (13 August 2012). "The 25 Greatest Rock Memoirs of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 188.

- ^ Stevens 2002, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Howlett 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Stevens 2002, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Spitz 2013, p. 108.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 192–93.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 173–74.

- ^ Giuliano 1997, p. 52.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 143–44.

- ^ Halpin, Michael (3 December 2015). "Rubber Soul – 50th Anniversary of The Beatles Classic Album". Louder Than War. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ a b Bellman 1998, p. 297.

- ^ a b Inglis 2010, p. 136.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 165fn.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 193.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 153.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 81.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 173, 174.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Kruth 2015, p. 78.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 161–62.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 132.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Kruth 2015, pp. 74.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2013, pp. 280–281.

- ^ a b Unterberger 2006, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles Anthology 2 review". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Ryan 2006, p. 397.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 165.

- ^ Spizer 2006.

- ^ Kruth 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Kruth 2015, p. 69.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 69, 200.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 215, 217.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles Rubber Soul review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 69.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 173.

- ^ Ovens, Don (dir. reviews & charts) (21 May 1966). "Billboard Hits of the World". Billboard. p. 42. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 204.

- ^ "Australia No. 1 Hits – 1960s". worldcharts.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ "British single certifications – Beatles – Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Norwegian Wood'". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (9 September 2009). "The Beatles Rubber Soul". Pitchfork. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Kruth 2015, p. 17.

- ^ Womack 2009, p. 79.

- ^ Bag, Shamik (20 January 2018). "The Beatles' magical mystery tour of India". Live Mint. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ a b Bellman 1998, p. 292.

- ^ Howlett 2009.

- ^ "John Lennon: The Rolling Stone Interview – 1968". Rolling Stone. 23 November 1968. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Perone 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 368–69.

- ^

Collaborations (Boxed set booklet). Ravi Shankar and George Harrison. Dark Horse Records. 2010.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Love You To' review". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Inglis 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Tillery 2011, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, pp. 177–78.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 243.

- ^ Lavezzoli 2006, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Phil; et al. (July 2006). "The 101 Greatest Beatles Songs". Mojo. p. 90.

- ^ Montgomery 2014, p. 65.

- ^ "These Indian covers of Norwegian Wood sound as distinctive today as the Beatles first 'sitar song'". Scroll.in. 11 October 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Strong, Martin C. (2000). The Great Rock Discography (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Mojo Books. pp. 750–51. ISBN 1-84195-017-3.

- ^ 11th Annual Grammy Awards, at Grammy.com. Retrieved 3 July 2017

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 314.

- ^ "British single certifications – The Beatles – Norwegian Wood". British Phonographic Industry.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bellman, Jonathan (1998). The Exotic in Western Music. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-319-1.

- Church, Joseph (2019). Rock in the Musical Theatre: A Guide for Singers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-094348-6.

- Decker, James M. (2009). ""Try thinking more": Rubber Soul and the Beatles' transformation of pop". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–89. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthrology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509553-7.

- Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men Through Rubber Soul. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514105-9.

- Giuliano, Geoffrey (1997). Dark Horse: The Life and Art of George Harrison. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80747-3.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Howlett, Kevin (2009). Rubber Soul (CD booklet). The Beatles. Parlophone Records.

- Inglis, Ian (2010). The Words and Music of George Harrison. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3.

- Kruth, John (2015). This Bird Has Flown: The Enduring Beauty of Rubber Soul, Fifty Years On. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-573-6.

- Jackson, Andrew (2015). 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-05962-8.

- Lavezzoli, Peter (2006). The Dawn of Indian Music in the West: Bhairavi. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1815-5.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London: Pimlico Books at Random House. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2013). All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release. Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-57912-952-1.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary, Volume 1: The Beatles Years. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8308-3.

- Montgomery, Ted (2014). The Beatles Through Headphones. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7863-7.

- Norman, Philip (2008). John Lennon: The Life. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-66100-3.

- Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. Omnibus Press.

- Perone, James E. (2012). The Album: A Guide to Pop Music's Most Provocative, Influential, and Important Creations. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-37906-2.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0.

- Ryan, Kevin (2006). Recording the Beatles: The Studio Equipment and Techniques Used to Create Their Classic Albums. Curvebender Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9785200-0-7.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Spitz, Bob (2013). "The British Invasion". Time.

- Spizer, Bruce (2006). The Capitol Albums, Volume 2 (CD booklet). The Beatles. Capitol Records.

- Stevens, John (2002). The Songs of John Lennon: The Beatles Years (1st ed.). Boston: Berklee Press. ISBN 0-634-01795-0.

- Tillery, Gary (2011). Working Class Mystic: A Spiritual Biography of George Harrison. Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0900-5.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: HarperLuxe. ISBN 978-0-06-249713-0.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Williams, Paul (2002). The Crawdaddy! Book: Writings (and Images) from the Magazine of Rock. Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-634-02958-4.

- Womack, Kennack (2009). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86965-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Sheff, David (2000). All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- Shepherd, John; Horn, David (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World Part 1– Performance and Production, Volume 2 (1st ed.). London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-6321-5.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-80352-9.